explore the world through the universal language of food

Cassava, the resilient crop

Cassava (yuca, medico, tapioca, manioc) is a starchy and tuberous root originating in the Americas.

It is the sixth most important crop in the world, feeding around 8000 million people a year. This hardy vegetable is a globally traded commodity with a deep history, long-withstanding versatility and a hopeful, sustainable future.

Origins and Early Domestication

This perennial shrub originated in the New World somewhere along the southwest border of the Amazon Basin between Southern Brazil and Eastern Bolivia. Its domesticated variety was discovered in the 19th Century and this particular varietal is estimated to be around 8000-10000 years old. It is one of the oldest cultivated crops that spread quickly throughout Central and South America and was eventually dispersed to Asia and Africa.

Cassava has been a significant crop of survival and symbolism for the Indigenous people of the Americas. For the Maukshi tribes of Guyana and Northeastern Brazil, it was a resilient food before, during and after colonisation and appeared in mythology and religious ceremonies. The Mayan civilisation was also responsible for the cultivation of cassava as well as its spread throughout the Americas.

The indigenous peoples learned how to prepare cassava (through trial and error and I expect possibly death), in a way that would reduce the toxicity of this nutritionally dense crop.

Unpeeled Cassava

Two common methods used to prepare cassava were to grate and strain the moisture and then allow it to dry and grind it into flour (farina), the second method is to peel, wash and boil it. The liquid from the cassava, once removed from the starch, can also be used after it has been fermented and then boiled for several days. This is known as tucupi, a unique product used in Brazilian dishes such as pato no tucupi (duck in tucupi) and tacapa (soup).

With a deep root system, the cassava crop is extremely resilient in adverse weather conditions and was integrated with other crops such as maize and beans.

In pre-Colombian times, cassava was an important commodity that was traded throughout the coastal and highland regions with other products cacao and maize. It was also used in various rituals and community gatherings.

The Colombian Exchange, a significant trade route established after Christopher Columbus voyaged to the New World in the late 1400s, moved cassava and other plants, diseases, cultures, and ideas from the Americas to Africa and eventually to the Old World.

Cassava in world cuisines

This diverse and multiple-use crop can be found in an abundance of dishes significant to cuisines around the world.

SOUTH AMERICA

Farofa, is a toasted cassava flour with butter, onions, sometimes bacon and spices. It serves as a side dish to grilled meats and theBraziliann favourite, feijoada, Pao de quejo, a sticky and cheesy snack is also made with cassava flour.

In Peru, cassava is often boiled, then fried until crispy as a side dish or on special occasions, is served in Juane, a type of Amazonian tamale that consists of rice, meat, spices, beans and eggs, blanketed in a bijao leaf and steamed for several hours.

Apart from making crispy cassava fries, Enyucado, a popular Colombian cake is the perfect bake to showcase this wonderful ingredient.

Casabe, is a bread made only from cassava is found in Colombia, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. The cassava is grated, dried and cooked until it forms together then served as a side dish or as a base for stews and sauces to be piled on top.

In Colombia, cassava is grated and made into a sweet cake called Enyucado

AFRICA

Fufu, a sticky dough in Nigeria consists of fermented cassava only, whereas in other Western African countries it is pounded with plantains and cocoyams. It is

Cassava flour in East Africa is used to thicken stews and the leaves of this crop is often included into stews and soups with coconut milk, vegetables and meat.

ASIA

In Asia, cassava can be seen in many sweet dishes and drinks like bubble tea, tapioca pudding with coconut milk and mango and getuk in Indonesia, a sticky sweet dessert that consists of palm sugar and cassava showered in grated fresh coconut. It is included in Meen curry in India and commonly sliced thinly and fried into crisps that are sprinkled with salt and chilli.

The cassava crop has fed civilisations for centuries and has withstood dramatic climate changes, its resilience has allowed it to be adaptable and to flourish in any continent around the world. Not only is it used in the culinary world, but it’s also industrial applications have made it an extremely sustainable resource, used for packaging, cosmetics and biofuel.

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Sopes - an Aztec Snack

Honestly, I had only tried sopes after living in Mexico for around 4 months and once I did, the world upon my palate changed.

It’s not a common street food, or so I thought, but I guess I was just not looking for them. I went to Cuernavaca for the weekend to spend it with my friend and his family to attend my first Mexican wedding which was quite the party and experience. The journey from Mexico City was not a long one, but a restless one so I had quite a long sleep and when I woke up and stepped into the kitchen, I sleepily saw a a glorious sope production line happening before my eyes.

My friend’s family had all come together from all corners of the world, and his mother was busy in the kitchen preparing food for 4 hungry boys, their partners and children. Not only was she making a mountain of sopes, but there was also a large bubbling pot of pozole to go along with them, needless to say, both were delicious, and I even enjoyed the tripe in the pozole (a traditional pork-based soup).

The sopes came together quickly and in all their simplicity they were unbelievably delicious, topped with straightforward and flavourful beans, cheese, queso fresco and hot sauce.

Sopes with black beans, avocado, cheese and hot sauce

One cannot talk about sopes without talking about maize and nixtamilsation. The maize crop was a fundamental element in Aztec societies and remains at the forefront of Mexican cuisine today. Even before colonisation, maize was processed by a method known as nixtamalisation. Treating the corn with alkaline solution (lime water), not only gave it a unique taste, but it also enhanced the nutritional content of the maize (specifically niacin), which was key to preventing pellagra.

Masa Harina is the dried flour of nixtamalised corn is the glorious ingredient that can be made from a myriad of corn types which can be transformed into cakes, tortillas, gorditas, tamales, champurrado and also, of course, sopes.

What Are Sopes??

Sopes are a much thicker version of a tortilla and are reasonably small in size (5-10cm), they have a ‘lip’ to hold ingredients that are layered on top of them, which range from beans, shredded pork, chicken, cheese, avocado, herbs and hot sauce.

They are not as common as tacos on the streets of Mexico, however, they are a more robust and portable snack, and just as delicious.

Masa harina (dough flour) is the base of sopes, which then has water added to it to create the dough. The dough is pressed, dry-fried, shaped and fried. There is no need to add salt or herbs to sopes. As simple as the base may seem, the process of nixtamilsation gives the corn an earthy and slightly tangy flavour profile.

The basis of sopes is essentially the same, however throughout the various regions of Mexico, everyone adds a variety of different toppings that reflect the colourful culinary diversity of the country.

Travel to Mexico city (De Effe), and you will find sopes piled high with papas con chorizo, potatoes and soft, slightly spicy Mexican chorizo. When you head south to Oaxaca, the culinary treasure of the country, sopes or memelas are showered with queso de oaxaca and sometimes crispy chapulines (grasshoppers). Jalisco’s sopes are earthy and deeply flavourful with slow-cooked meat stews such as birria. In Yucatan, sopes are brighter in flavour, yet robust with famous pork dishes such as cochinita pibil.

If you do travel to Mexico, make sure you try this wonderful dish that is robust, flavourful, and you can never ever stop at just one!!

If you can get your hands upon some good masa harina you can always try your hand at making sopes at home…. I made mine with black beans, avocado and cheese.

Cochinita Pibil

Credit @meridadeyucatan

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Ajiaco - Colombian Chicken Soup.

As I sat in a small restaurant in Bogota, I looked around at the homely interior, strong wooden furniture, slightly kitsch decorations, and a proud Colombian flag hanging over the ‘bar’. All the tables overlooked the live entertainment; a small cobblestone sidewalk filled with an occasional tourist, carts selling cocadas, and vendors selling small handicrafts.

The simplicity of Colombia, its beautiful landscape, her coloured yet troubled history, and straightforward food all encompass a unique experience to anyone passing through, or staying a while….

A rather plump older lady places a heavy terracotta bowl of stew (slash) soup in front of me with two hands, then a plate of rice with an extremely buttery sliced avocado. I dipped the large spoon into the soup and tasted it. There was warmth and comfort in this thick flavourful broth that was creamy with just enough acidity – although the flavour combination was rather foreign to me, it felt somehow familiar and remains to this day one of my favourite Colombian dishes I have ever tasted.

The very name of this soup, Ajiaco, includes the word Aji, meaning chilli pepper, in the language of the Taino people. Taino were Indigenous inhabitants that migrated from the north coast of South America and spread throughout the Caribbean, they were the most predominant society in the region before European contact in the late 15th Century.

The Taino people lived in a hierarchical society that crafted tools, boats and ornaments, worshipped deities of natural elements such as Yucahu the god of cassava and the sea, and ate an abundant diet of seafood, cassava, beans, maize, peppers, wild plants and hunted meat.

Ajiaco is a traditional soup that has evolved with the history and culinary landscape of Colombia. More than a soup, it is a stew consisting of filling ingredients that is perfect for cooler seasons and is accompanied by a variety of sides making it a very substantial meal.

The most popular Ajiaco is found in Bogota, and is known as Ajiaco Santafereño. The main ingredients in this Ajiaco are chicken on the bone to extract the hearty collagen and fat, three types of potatoes (criollas/yellow, sabaneras/red, pastusas/white), guascas, an extremely aromatic Colombian herb, corn on the cob, cream, capers and avocado.

Travel around Colombia and you will find variations of Ajiaco – in the Cauca Valley, the dish is extremely herbaceous, using a variety of plants from the region, in the north, along the Caribbean coast, you will find coconut milk in the dish which gives it a milder taste, whereas in the mountainous region of Antioquia, it is hearty and filled with many root vegetables.

The unique ingredients found in Colombian Ajiaco - Guasca and three types of Colombian potatoes

Guasca

Credit @amigofoods

Saberna, Criolla and Pastusa Potatoes of Colombia

Credit @ATouchofRoJo

Ajiaco, although most recognised to be a Colombian dish, can be found with slight variations in Cuba, Venezuela and Peru.

Ajiaco Cubano is robust and complete containing many root vegetables such as cassava, malanga, sweet potatoes, potatoes and different meats like beef, chicken, pork and chorizo. The heavier spiced flavour is a result of the addition of cumin, oregano, bay leaves, and paprika and it is full of plantains, tomatoes, corn, garlic, onion, coriander and peppers (capsicums).

Venezuelan ajiaco contains beef and pork and more vegetables and fruit such as carrots, plantains, corn, and tomatoes, and is flavoured with coriander, garlic, onions, cumin and oregano.

The significant difference of Peruvian Ajiaco to its Colombian counterpart Is the addition of huacatay (black mint), coriander and aji Amarillo (yellow chilli).

Whether you try this dish in Columbia, Cuba, Venezuela or Peru, Ajiaco is a humble stew that reflects the tradition of the indigenous people, demonstrates the vast abundance of ingredients throughout Latin America and reflects history in every, delicious bite.

Every version of Ajiaco whether in Colombia, Cuba, Venezuela or Peru reflects a variety of significant ingredients to that country. A humble stew that tells tales tradition from the indigenous people, and a varied agricultural landscape and reflects history beautifully in an extremely delicious way.

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Gula Melaka

Gula Melaka is a rich, caramel-like, unrefined sugar derived from the palm tree. It is named after the Malaysian state, Melaka, and is a common ingredient found in Southeast Asian dishes, in particular, sweets and desserts.

How is it made?

Made from the sap of the flower buds of the coconut palm, the first process of making gula Melaka is to tap the flower buds, making a small incision in the flower stalk, the sap is drained and collected. This sweet, unrefined liquid is also known as Neera, which is collected once or twice a day and cannot be kept unattended for some time as it is highly susceptible to fermentation. The Indigenous tribes that used to collect this sap learned that heating it to allow the water content to evaporate found longevity in this sweet and natural product. This process is a significant and lengthy process for the result of Gula Melaka, taking up to 7 hours. When the sap becomes a dark–syrupy colour and consistency, it is then poured into molds, traditionally bamboo or coconut shells are used for this. The syrup hardens, resulting in a firm, sweet block of Gula Melaka.

Gula Melaka travels the world

Gula Melaka accompanied spices and textiles from Southeast Asia through to India, China and beyond. Europe via trade routes. The most important was the Maritime Silk Roads that extended 15,000 km connecting the East to the West. They stretched from the western coastal areas of Japan to the Indonesian islands, around India and into the Middle East, and eventually the Mediterranean and Europe. Significant ports in Southeast Asia around the 15th and 16th Century were Malacca, Aceh, and Java. The European colonisation in the 16th Century, notably the British, Portuguese, and Dutch, also was a significant catalyst for moving this specialty sweet gold, gula Melaka, from Southeast Asia to Europe.

The dark, caramel taste and texture of pure Gula Melaka, make it a versatile ingredient that can be added to traditional cakes and desserts such as kueh, cendol, ondeh ondeh and sago puddings. It adds depth to sambals, sauces, and marinades.

A simple but pure ingredient that is steeped in tradition, brings together community and unique flavours for celebratory dishes, everyday enjoyment and sweet indulgence.

Hello

SOME SWEET RECIPES…..

Congee Around Asia

My memory was jogged today as I positioned myself in front of the laptop to write about the time I sat and savoured a bowl of Cháo Sườn (pork rib rice porridge), on a small plastic stool by the busy roadside in the Old Quarter, Hanoi.

A simple pot of rice porridge was being stirred over coals by an old Aunt and as she stirred the simmering rice, glimpses of pork emerged to the surface. She scooped a good ladle or two of it into a plastic bowl, covering the freshly cracked egg, and then topped it with scissor-cut fried dough sticks (quẩy) and a generous helping of pork floss (ruốc)

The honking symphony of the scooters, the footsteps of tourists and the chatter of the Vietnamese vendors around the street stall was a simple and raw setting, just as street food should be enjoyed. I found stillness and comfort in eating this centuries-old dish that has been made in a multitude of households and countries since its first documented recordings during the Zhou Dynasty (1000BC).

‘Congee’ is a derivative of the Tamil word ‘Kanji’ that was since changed by the Portuguese and came full circle to be known as Zhou/Congee. It is one of the simplest dishes you will find on your travels throughout Asia, yet every person who cooks it in every country puts their spin on flavours, and textures from lugaw arroz caldo in the Philippines, bor bor in Cambodia, kanji in India, or chok/jok in Thailand.

What is Congee?

Congee is a savoury rice porridge that is made by boiling rice in water or bone broth until the grains are completely softened and can still either be recognised, or they have been cooked down to resemble a type of white gruel. In some parts of Asia, it is also made with other grains such as millet, sorghum and barley. Congee is a dish that has been used to feed those in famine or settle an upset stomach and can be eaten at any time of the day. In Asia, rice porridge is popular for breakfast and can also be eaten as a side dish. The texture and individuality of a congee or rice porridge are in the base broth, type of rice/grain used, meat, toppings and finishing sauces and herbs.

China

Congee in China varies from region to region due to the availability of grains and ingredients. Cantonese congee in Guangzhou uses white rice and is decorated with century egg, beef, fish, or salted pork and peanuts with white pepper and soy sauce. Teochew porridge is light, and the rice grains remain separated and is served alongside small cooked and pickled side dishes of meat and vegetables. Hakka rice congee combines glutinous rice with white rice and contains heavier flavoured proteins such as pork belly and dried cuttlefish. The congee of Shanghai combines both rice and grains (usually millet), and is eaten with preserved vegetables, shredded tofu skin, and pork.

A significant type of congee is Laba, which is a traditional congee eaten on the eighth day of the twelfth month in the Chinese calendar and contains grains, beans, nuts, and fruit.

Laba Congee

Credit: Omnivore’s Cookbook

Cambodia

Cambodian borbor is more of a rice soup than a porridge where the grains of rice, usually Jasmine, swim around the bowl separately to take on the flavour of the stock which is commonly made from either pork or chicken.

The umami broth is sometimes boosted by dried preserved seafood and a pinch of MSG.

Borbor can be topped with shredded Khmer chicken (link to Khmer chicken), pork or even fish. It is optionally served with cha kway (fried dough sticks) and all the typical Cambodian condiments which adorn each table of any eatery (lime, fermented soy beans, pickled fresh chillies, red chilli sauce). Pair bor bor with an iced local coffee and you are set for the rest of the day.

Learn a little bit more about Cambodian bor bor HERE.

Nanakusa Gayu (7 herbs rice porridge)

Credit @justonecookbook

Japan

Japanese Okayu is a rather thick rice porridge that is usually made with polished short-grain white rice or sushi rice known as hakumai. The Japanese have used okayu for feeding babies, the elderly and also individuals with digestion issues. Some ingredients such as roe, salmon, umeboshi or egg can be added to okayu and the both is sometimes flavoured with dashi or miso. Influenced by the Southern Chinese tradition of preparing soup with 7 vegetables on the 1st Chinese calendar month, the Nanakusa no sekku (festival of the seven herbs), uses seven herbs in the Okayu and is known as Nanakusa-gayu.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s bubur ayam is a congee that takes your palate on a journey of flavours and textures. It breaks the mould of traditional rice porridge and is an extremely popular street food throughout Indonesia, particularly for breakfast. Each region in Indonesia has its own variations, but it is essentially a strongly flavoured chicken rice porridge. Shredded chicken is added, along with a myriad of textures and tastes such as roasted peanuts, fried scallions, green onions, cakwe (fried dough sticks), kerupuk (crackers), soy sauce, sesame oil and sometimes fish sauce. . It is not known as a spicy dish, however, there is always a little bit of sambal that is served on the side.

Thailand

Thailand’s Chok/Jok is an extremely smooth porridge that uses broken Jasmine rice and typically uses either pork (jok moo) or chicken (jok gai) to flavour it. The rice is cooked with water until an oatmeal consistency and gathers flavour, texture and colour from ingredients of pork meatballs and offal or chicken, soft-boiled egg, fried garlic, thinly sliced ginger, spring onions, a dash of soy sauce and a dusting of white pepper.

Philippines

Lugaw is the umbrella term for the Phillipino version of rice porridge which can be savoury or sweet and use a variety of meats such as chicken, beef, pork fish and frog. The sweeter versions of lugaw contain chocolate (champurrado) or corn (ginataaing mais).

Lugaw arroz caldo is the chicken version that uses sticky rice to make the porridge. The rice is seared in oil with the rice, ginger, garlic and onion and then brought to a simmering boil until the grains have broken down into a soupy texture. Arroz caldo is tinctured with a saffron like colour that is imparted by kasubha (dried safflower).

The extremely savoury, meaty arroz caldo is topped with fried garlic, boiled eggs, spring onions, a splash of fish sauce and a generous squeeze of calamansi.

Chicken Arroz Caldo (Philippines)

Credit @panlasangpinoy

Chok/Jok from (Thailand)

Paal Kanji (India)

Credit @yummytummyaarthi

India

In the vast country of India, many types of Kanji or rice porridges use a variety of rice and including lentils or beans. Other ingredients used in Indian kanji include milk, curd, and coconut as well as a finishing touch of tempered herbs, spices or chillies. A rice porridge known as khichdi is a mixture of rice and moong dal and has been used as a prescription food for centuries in Ayurvedic medicine.

Vietnam

Vietnam’s Cháo is extremely simple, yet one of my favourite rice porridge dishes in the region and comes in many varieties. It is cooked predominately with short-grain rice and water until it is a medium-thick consistency where the grains have completely broken down. Chao can contain pork offal, duck, mushroom, pork meatballs and mushrooms. It is dressed with meat floss to give an airy and chewy texture, partially cooked egg, green onions, crispy garlic, century egg, and soy sauce.

It is essential to pair it with quay (fried dough) to dip and wipe every last morsel of this tasty dish that is served not only for breakfast but throughout the entire day for sustenance and absolute pleasure.

The history of congee is extensive and its popularity in so many countries that have adopted this simple and humble dish and made it their own is a testament that it is one of the ultimate comfort foods that can make you feel better and transport you to a place of happiness and content in both your belly and your tastebuds.

Wherever you travel in Asia, make sure you seek out a bowl of congee, and if you aren’t travelling anytime soon, you can always make this simple fish congee recipe using Hong Spices white pepper seasoning.

Hello, World!

Cháo Sườn in Hanoi

Simply Delicious Cacio e Pepe

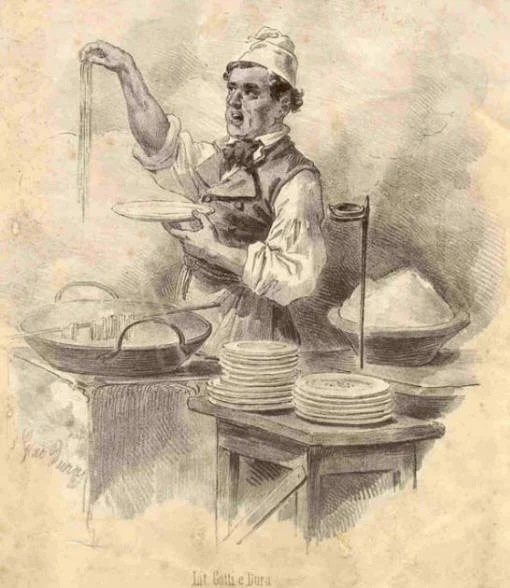

A tangled shiny tower of long tonnarelli strands, embraced in a thin yet visible coating of sauce is placed down in front of me right next to my glass of Montepulciano.

I look down at the simplicity of this dish and a rush of sheer giddiness overcomes me, I look around and smile triumphantly to myself, and plunge my fork into the glorious mess. Catching a few strands of the long rectangular spaghetti and twirling it around my fork (no spoons here!), I bite into the perfectly cooked pasta and savour the salty cheese sauce that is speckled with heat from toasted black pepper.

As simple as it appears to be, there is a whole lot that can go wrong with this traditional Roman dish, but when it is executed beautifully, it instils a lifelong memory that you can store forever in your palate’s flavour bank.

Cacio e Pepe. How can such a simple dish of cheese, pasta, and pepper be so memorable and popular, being served in its true form and thousands of other variations all around the world? Good food doesn’t have to be complicated and can be accessible to everyone.

There is a wonderful story of shepherds in the Apennine Mountains carrying dried pasta for a filling meal and pepper to help stimulate and warm them in the winter months. With the addition of cheese made from the milk of the sheep they were herding, the infamous cacio e pepe was invented.

It is more likely this Roman peasant dish was one of sustenance for the factory and mine workers on the outskirts of the Lazio region. Although pasta has been around in Italy since the 1300s, it was not an accessible food source as it is today. Prior to the 1800s, the lower class was more likely to have consumed bread and polenta while the elite societies enjoyed pasta. Rather than a vessel carrying delicious cheese and sauces, pasta was usually overcooked nestled amongst meat, vegetables, spices, herbs, and even fruit.

Cacio e Pepe was probably invented around the 1800s post-unification of Italy when pasta became a popular staple amongst the majority. The popularity of pasta most likely started in Sicily and Naples where wheat was sold relatively cheaply and it eventually spread throughout other regions of the country when meat became extremely scarce. Pasta then was industrialised during the 17th century when the torchio machine was invented, enabling pasta to be made in larger quantities.

Over the years the dish has morphed into many variations that even use Parmigiano Reggiano, resulting in a sweeter and nutty finish. Cacio e pepe has become an inspiration for many dishes such as ice cream, biscuits, pizza, and also risotto.

The Anatomy of Cacio e Pepe

Pasta

The pasta, tonnarelli or spaghetti alla chittara, is cooked in salty boiling water until springy and al dente.

Cheese

Cacio, meaning cheese is what brings a unique flavour to this Roman dish. Pecorino Romano, a sharp-tasting salty cheese made from 100% sheep milk is finely grated and mixed with a small amount of starchy pasta water until it has emulsified and made a ‘sauce’.

Pepper

The pasta is added to the ‘sauce’ and tossed a final time with toasted crushed black pepper, adding both warmth and spice to finish off the dish.

And that is all there is to it. simple, right?

If you haven’t tried Cacio e Pepe, I implore you to give it a shot and see how it tastes, serve it with a simple salad and a glass of your favourite white or red. It is one of the most comforting and simple dishes that has ever been invented and is truly one of my ultimate comfort foods (among others).

Try this delicious version of cacio e pepe here at An Italian in My Kitchen

Credit: An Italian in my kitchen

Or have some fun with these cacio e pepe crackers

A Short History of Cumin

As I was making my Sunday rounds at the markets, I spotted a beautiful bunch of baby carrots and immediately I just wanted them to roll around in a warm bath of salted butter, cumin, and a titch of honey. So that’s just what I did.

Cumin is not only my favourite spice, but also a historically important one that has been used for thousands of years. Despite some articles you may have read, cumin, the brown little wormy-looking seeds, which are readily available in markets and supermarkets, is not the same spice used in the mummification process of ancient Egypt. This type of cumin is known as Nigella Sativa or black cumin and has nothing to do with the brown cumin that is common in Latin, Indian, and Middle Eastern cuisines.

From feasts in northern Iraq around the 9th Century to Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, cumin has been documented to be used widely as a flavouring and natural medicine to cure or ease a variety of ailments such as digestive problems. From its origins in Mesopotamia, cumin moved through Europe as a spice, a medicine, and even as a currency in Medieval England where it was used to pay rent.

The Colombian Exchange, instigated by Italian Explorer Christopher Columbus began in the late 15th Century and initiated the transference of many food products from the old world to the new and vice versa. Animals, plants, cotton, sugar, and spices were some of the products that were traded along this route, cumin was one of them that made the voyage and embedded itself into a variety of cuisines in the Americas.

Despite being known as a spice, the cumin seed is actually a fruit derived from a small flowering plant technically known as Cuminum cyminum and is from the same family of dill, parsley, and carrot (no wonder they go so well together!).

The ‘roasty’ flavour of cumin has a slightly citrus tang on the tongue combined with warmth like cinnamon and invites complimentary spices like coriander, chilli, and turmeric. It is commonly used in savoury dishes but adds a wonderful layer of flavour to sweet dishes as well.

It is a small but powerful seed that helps stimulate digestive enzymes, aids the body in absorbing minerals, and is also known as an anti-inflammatory. Hot cumin water with a dash of honey is a wonderful way to start the day. It is also an element of modern-day pharmaceuticals and is used in aromatherapy.

From Mexico to India, Greece, and Turkey, cumin is one of the most widely used spices in cuisines around the world and adds a unique profile to any dish whether it be a soup, tagine, salad, or even tea!

Cumin is predominately grown in India, providing 70% of the seed to the world, however, it is also cultivated in North Africa, Turkey, the Mediterranean, Mexico, and the Middle East.

Cumin was and still is an extremely important commodity that can be grown in arid to semi-arid terrain, which allows it to be subject to sustainable agricultural practices. It is, however, an extremely labour-intensive crop that is usually hand harvested 120 days from when the seed is planted.

As with all ingredients put down before us, we should celebrate the history and the people who made it possible for us to be exposed to such diverse ingredients wherever we are in the world. Cumin, one of the first written recorded spices in the world is a special one and I encourage you to experiment with incorporating it in a recipe or two, enabling you to understand its wonderful flavour, warmth, and diversity.

Try experimenting with these main dishes….

The History of Food and Cuisine in North America

The Americas today is extremely diverse in culture, food, traditions, and cuisine. By exploring how and when humans migrated to the Americas and dissipated throughout the region, a beautiful pattern of ingredients spread across this vast expanse of land and then to the rest of the world.

From the nomadic communities who first travelled across the Bering Strait, to the Eastern Woodland People and the impact of the transatlantic slave trade, the land became dotted with a plethora of wonderful produce. Avocados, tomatoes, potatoes, allspice, black walnuts, and cacao are just a few of the ingredients we enjoy throughout the world. Every ingredient has a journey, every dish has a story, and here is a little introduction to the beginning history of food and cuisine in North America.

The New World is known as one of the last areas in the world to be inhabited by humans. People of Asiatic descent were originally thought to have travelled by land along the Bering Strait (the strait that links the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Sea) in the North. However, the latest anthropological research has revealed humans may have ventured out before this by boat, travelling along the Pacific shore of what is known as the Kelp Highway somewhere around 15,000-20,000 years ago.

Image as above from worldatlas.com

Originally, the people who first migrated to the Americas were isolated nomadic communities living off megafauna and native food plants. Through either climatic changes or human action, the extinction of around 60 megafauna species dramatically changed the diet and lifestyle of these once-hunter-gatherers. Most of their diets suddenly became reliant on agricultural means and they slowly cultivated and hybridised food crops that are found in every cuisine around the world.

Tribes were spread throughout the Americas, and strong communities and civilisations began to form at centralised trade routes. Canada, as we know it today, was covered in ice for some time and most probably was the last part of the Americas to be inhabited by humans.

The Eastern Woodlands People

The Eastern Woodlands People that settled in the North-Eastern part of America as well as those on the West Coast, formed communities that were sophisticated culturally, politically, and socially. Their diets consisted of wild game and many different plant species. Maple syrup was also discovered in this region and today is one of the most popular indigenous ingredients of America that is consumed worldwide.

Eastern Woodlands People. Credit - Unknown

The tribes that moved throughout North and South America were the Cahokia along the Mississippi River, the Incas in the Peruvian Andes, and the Aztecs in Tenochtitlan, Mexico. The varying locations of these tribes depicted the type of food they consumed whether it be seafood (turtles, fish, crustaceans), meat (bison, other game, possum, turkey), nuts, or berries.

One ancient planting system that provided staple ingredients to the Native American diet all year round was called the ‘Milpa’ or ‘Three Sisters’ crop. The trio of plants grown together provided an entire system of replenishing the soil with nitrogen, encouraging plant growth, allowing it to climb as well as providing shade for the soil, keeping it moist and a deterrent for weeds. The three sisters’ crop was found throughout the Americas and the use of corn, bean, and squash was significant to both the North and South American diets.

The ingredients available to the Native Americans were abundant and the fertile earth ensured a luscious, agriculturally forward, yet varied diet, even before European settlement. Native Americans made nutritionally complete dishes, cooking most ingredients by boiling or roasting over an open fire.

Ingredient Origins in the Americas

Below are some of the ingredients that originated in the various regions of the Americas. This produce spread throughout, ensuring a varied and palatable diet.

North America

Jerusalem artichoke, pumpkin, a variety of squash, beans (black turtle, navy pinto, cranberry), black raspberries, blueberries, cranberries, wild rice, black walnut, bison, sunflower seeds, turkey, maple syrup, pecans.

Cranberry Beans. Credit @gabriella.claire

Black Rasperries. Credit @Ulvi Safari

Central America and Mexico

Sweet potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, corn, allspice, avocados, chillies, bell peppers, and vanilla.

South America

Lima beans and other bean varietals, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, quinoa, cashew, peanuts, and cassava.

Potatoes. Credit @Markus Spiske

Tomatoes. Credit @Empreinte

Peanuts. Credit @me !

Corn was used extensively in many Native American dishes such as Sofkee (a dried corn porridge) and a simple version of Succotash (a corn and bean dish). The Native Americans ate well due to the wide variety of ingredients available in both the North and the South. A type of bread was made such as cornbread, cornbread with beans, and fry bread. Squash was used in stews and soups, as was fish that was roasted or fried. Cherokee fish and corn mush are dishes that still exist today, as well as altered versions of baked beans.

The indigenous Canadian diet included seal, whale, polar bear, buffalo, caribou, and vegetables. It was extremely high in calories to combat the freezing climate, and many ingredients were harvested, dried, and preserved to be eaten in the long winter months. Pemmican (dried meat and berries), maple syrup, and muktuk (dried whale blubber) were all consumed by the indigenous peoples.

The first Europeans in North America were Norsemen (Vikings) of Greenland, settling for a short period in Newfoundland, about 500 years before Christopher Columbus.

The arrival of the Europeans in the late 15th Century had a dramatic effect both on the native people of the Americas as well as on the environmental and culinary landscape. Crops and animals that were brought from the Old World thrived in the New World and vice versa. It was not only the transference of ingredients that changed American cuisine, it was also the people, commodities, and technology that contributed greatly to its evolution.

Soon after the arrival of Christoper Columbus in 1492, the Columbian Exchange was established. It was a global transference of plants, animals, people, technology, and disease between the Old World and the New World and not only impacted the countries directly involved but the whole world both positively and negatively. It changed the people, the landscape, and the climate of the Americas.

The Colombian Exchange. Credit @reconcilliationsofnations.com

Native crops of the Americas such as corn, tomatoes, cassava, potatoes, cacao, and chillies were important ingredients within the exchange and have become staples in many global cuisines of today.

Some of the European crops that were brought over from the Old World such as wheat, rice, spices, citrus, and bananas, thrived and redesigned many dishes and cuisines of the Natives. Unfortunately, with so much movement of crops, animals, and people between the old and new world, diseases were rife. The Native Americans had never been exposed to viruses or bacteria such as smallpox, typhus, measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, or cholera. The transference of these diseases was carried through humans and animals and as a result, rapidly diminished the Native American population by around 80-90 percent within the first 150 years.

The first Dutch colony of America was established in 1624. It was known as New Amsterdam which is the area where New York City sits today. Small parts of Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey were also included as part of the New Netherlands, however, it eventually was taken over by the British and became one of the 13 colonies. These British Colonies remained quite traditional in the dishes they cooked, which were typically either boiled or fried. The game was popular and used to make soups, stews, or even preserved or dried, animal fat was used for cooking and corn was an ingredient commonly used. Colonies close to the ocean enjoyed a diet rich in fish and Crustaceans.

New France, was the first colonisation of the French in North America and reflected traditional French fare with eh adaption of climate, availability of ingredients, the necessity to be resourceful, and the hardship of colonial life. As New France was eventually succeeded by British rule, the cuisine became heavily influenced by the English and Irish styles of cooking. Salt-cured meats, and seafood such as mussels, trout, salmon, lobsters, and eel were popular and abundant.

As the Native American population reduced dramatically due to the rapid spread of disease by the Europeans, the fertile expansive land of the New World required more labour for the agricultural industry to flourish. There was a growing need for workers to be placed on commodity plantations, in particular the sugar cane fields, an old-world crop that flourished in the fertile land of America.

Slave Trade

The Atlantic Slave Trade, the largest involuntary migration in history, was the importation of over twelve million African slaves to the New World from the 16th - 19th Century. Most slaves were sent to work in South America and the Caribbean, while only 5% were exported to North America. The slaves in North America worked mainly in the South as labourers on large plantations (cotton, rice, tobacco), small farms, domestic workers (cooks, servants, carers), and drivers.

The Slave Trade. Credit @thelibraryofcongress

Cooks of the household were on call every hour of every day, feeding the household, guests that would drop by, as well as the workers of the house and property. Southern Cuisine began in the kitchens of these enslaved Africans and has evolved to be a historically rich and significant cuisine in America.

Corn was used heavily used in Southern cooking and can be used to make a variety of dishes such as cornbread, grits, dumplings, and even alcohol. Small game meats and innards (chitterlings) were common as well as beef and pork. Other notable ingredients such as Okra, beans, cayenne peppers, and rice also reflected African cooking. Food was still cooked over open fires, or boiled and fried.

The cuisine of North America has evolved from simple British cooking and ingredients to an abundant culturally rich one, comprising of dishes that each have their place in time. Each dish or ingredient tells a story of immigration patterns, native food cultures, human adversity and the crossing of cultures from all over the world. The colonisation of America has also blended a variety of cooking techniques that still exist today including grilling meats over an open fire, spit-roasting and cooking root vegetables directly over ashes.

Achiote. Tales of the Lipstick Tree.

A cluster of small and hairy, rusty red heart-shaped fruits sit nestled amongst the branches of a 5-metre tree, waiting to pop open and reveal its vibrant flesh and seeds. The meaty part of this fruit is inedible, but the seeds have been used for centuries in many applications. This is achiote, also known as annatto, and has been used in cosmetics, as a textile dye for textiles, and as a natural additive to food for thousands of years. The beautiful colour and unique flavour of achiote has found its way into many dishes around the world.

The Origins of Achiote

Achiote stems from the Nahuatl word āchiotl and is formally known as Bixa Orellana. In the English-speaking world, it is also known as annatto, yet this is technically a name to describe the colour that is derived from the seed. Achiote finds its roots in Central and South America, with Peru, today producing the majority of the world’s supply.

Due to the complex genetic makeup of the plant, it is impossible to generate new strains, therefore there is only one type of achiote in the world, yet each can differ slightly depending on environmental circumstances.

Achiote History - from ancient civilisation to the rest of the world

Achiote was symbolically used in Mayan and Aztec ceremonies and rituals, representing blood, fertility, and the vibrancy of life. The seeds were also ground into a paste and added to a variety of dishes, creating a distinctive flavour and colour. When the seeds were soaked for a period of time, the liquid obtained a beautiful red which was then used to dye textiles. Other parts of the plant such as were also used as natural remedies to cure a variety of ailments such as inflammation or digestive disorders.

Intrigued by these wonderous plants, the Portuguese and Spanish explorers decided to take them back to Europe in hopes to trade them as an exotic commodity. As trade routes opened connecting the Americas to Asia, achiote travelled initially to the Philippines via the Manilla Galleon Trade route that began in 1565. This significant trade route which lasted for around 250 years, connected Acapulco in Mexico to Manilla in the Philippines and was one of the largest world exchanges of spices, people, porcelain and precious metals in history.

Once achiote arrived in the Philippines it was adapted into their cooking, which inspired interest from Indonesia and other neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia. Through sea trade routes, it spread to Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

As colonisation in the Caribbean took place from the 15th Century onwards, the Caribbeans started incorporating achiote as a colouring and as a paste for marinating meats. The Transatlantic Slave trade also impelled Africans to work in the Caribbean and Americas as plantation workers and servants, enabling the exchange of commodities, including achiote.

Credit: sweetlifebake.com

What does achiote taste like and how to use it?

Achiote has a subtle floral and peppery taste, providing warmth to dishes like nutmeg. Despite its mild taste, adding achiote to a dish can transform it tremendously. It is used as a popular food dye to colour cheeses, candy, ice cream, and various meat products.

It can be used as a marinade for cochinita pibil, a Yucatecan speciality in Mexico, added to Brasilian fish moqueca, infused in Puerto Rican arroz con pollo or added to a Filipino Kare Kare.

The seeds of the achiote fruit can be used as is or are treated in several ways to extract optimal colour and flavour before it is used as a culinary ingredient.

Popular preparations of achiote seeds before incorporating them into a dish are:

Achiote Oil or Water

The seeds are submerged in oil or water and heated to impart colour and a touch of flavour.

Achiote paste

Vinegar is used with ground seeds and additional herbs or spices to form a paste.

Achiotina

Is the result of a flavour and colour extraction through heated animal lard.

Non-Culinary Uses

The achiote fruit and leaves are used in a variety of cultures around the world as a diuretic, wound dressing, anti-venom, and even a cure for muscle aches and pains. In a more altered form, it is used widely to colour creams and lipsticks in the cosmetic industry and as an additive to a variety of medicines.

This wondrous little plant has managed to place itself subtly into all the corners of the world, through a history of colonisation, trade routes, and cultural exchanges over many years. Achiote is another beautiful example of how food history and culture are so interconnected and can tell exciting tales that evolve over time.

Brazilian Cuisine - A Delicious Blend of Cultures and Flavours

Brazil has a wonderfully rich history and vibrant culture that has been shaped over time by a variety of influences starting from the Indigenous people to the immigrants of Africa, Europe, and also Asia. Let’s go on a little expedition to explore ingredients native to the country as well as the delicious dishes that are found in the varied regions of the country.

Brazil is a geographically diverse country, it sits beside the Atlantic Ocean and borders every South American country, except for Ecuador and Chile. Being such a large country, the climate differs greatly throughout, and it contains some of the world’s most amazing, complex ecosystems such as the Amazon Rainforest, The Atlantic Forest, the Cerrado, and the Araucaria Pine Forest.

It is the largest country in Latin America governed as a democratic public officially known as the “Federative Republic of Brazil”. Brazil differentiates itself from its fellow South American counterparts, as it was the only country colonised by the Portuguese. These explorers in the early 16th Century gave the country its name ‘Brazil’ which is derived from the Portuguese word meaning ‘Brazilwood’, a redwood tree that grew abundantly throughout the coastal region of the country and was used for making dyes in the European textile industry. that was used to make dies for the textile industry in Europe. The word Brazil comes from the Brazilwood tree that once grew in abundance throughout the coastal region of the country.

What is Brazilian Cuisine?

Brazilian cuisine can be characterised by its regional differences and the unique cultural influences of the Indigenous people as well as immigrants from Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Indigenous Influence

The native people of Brazil were hunter-gatherers whose diet contained fish, meat, and ingredients that were harvested from the land. Food was cooked and preserved using a variety of methods, and it was also important in cultural and spiritual rituals and ceremonies. The cooking methods of the native Brazilians such as cooking over an open fire or pit roasting were simple yet effective and are still practices that are used today, particularly in the Northern regions of the country.

The Native Crops and Ingredients of Brazil

The basic crops the Indigenous people cultivated and ate before the arrival of the Portuguese in the 1500s were calorific, medicinal, and, abundant. The Indigenous diet was so unique and plentiful, and it still plays a significant role in modern Brazilian cuisine today.

Cassava (Manioc/Yuca)

Cassava has always been an important staple food in Brazil, and continues to be even to this day. Cassava, also known as manioc, mandioca, or yuca, is a root vegetable that is dense in carbohydrates and calories and can be stored over a long period of time. It is cooked by boiling or frying and can also be dehydrated and ground into tapioca flour.

image of cassava

Tucupi

Tucupi is a bi-product of cassava the indigenous people used in their diet. It is a fermented yellowish-brown liquid that is extracted from the cassava root after it has been soaked in water or grated and then strained. Tucupi contains a high concentration of cyanide and must be boiled prior to consumption. It is a unique ingredient that is still used in Brazilian dishes. I learned about this black version of tucupi which is being used in the modern culinary world of Brazil.

Corn

Corn was also a stable crop to the native Brazilians, particularly in the Southern regions where it was roasted, boiled, or even ground down into a meal to make bread or porridge.

Cumaru/Tonka Bean

Image @(www.candlescience.com)

Cashews

Native to North-eastern Brazil, the cashew tree provided nutritious protein, minerals, and vitamins to the indigenous diet. Both the cashew nut and its fruit were consumed not just as food but for medicinal purposes as well.

Cumaru

Cumaru or Tonka Bean is a tree native to the Amazon rainforest and is from the pea family that produces a dark fruit containing seeds that were used as a spice by the indigenous Brazilians. With slightly smoky, almond, vanilla, and cinnamon notes, it was used to flavour meat dishes and was also used for medicinal purposes to help cure coughs and fever.

Acai

Acai is a small, deep purple round fruit that grows on small acai palm trees. It was officially announced as a superfood in 2004, yet the Brazilian indigenous people have been using it long before the Europeans settled in the country. For thousands of years, the Acai was used as a medicine to cure many ailments. It is harvested by hand from the top of the palm and then made into a paste.

Credit: Guarana ( www.bluemacawflora.com)

Guarana

Another native plant to the wonderous Amazonian rainforest, Guarana is a climbing plant related to the maple family. Its peculiar seeds that look like eyes have a stimulating effect on the body, containing a concentrated amount of caffeine. Natives used to dry guarana, grind it into a paste, and drink it as a stimulant and also a cure for headaches and fever.

The Introduction of European Ingredients

The official colonisation of Brazil was in the 16th Century and it was the only country in South America to be claimed by the Portuguese. Ingredients such as wheat, sugar, and dairy as well as a variety of cooking techniques blended with traditional foods to create wonderful dishes such as feijoada (a pork and bean stew served with farofa and collared greens), bacalao (salted cod), and Pão de Queijo (cheese bread made with cassava flour). Olive oil, citrus, vinegars, wine and warm spices of cinnamon and clove were incorporated to add more depth to dishes. Other Europeans that migrated and had an influence on Brazilian cuisine within the 1500-1800s were the Spaniards, Germans, Italians, Swiss and Polish.

African Influence in Brazilian Cuisine

During the 16th to 18th Centuries, Africans were taken from their country to work on a variety of crop plantations in Brazil, notably sugar cane and coffee. The transatlantic slave trade lasted for such a long period of time which significantly impacted Brazilian cuisine and cultures, particularly along the coastal regions of the country.

The Africans brought to Brazil new cooking techniques and flavours and combined them with existing dishes, once again evolving the cuisine. The use of cooking in dendê (palm oil) has become a tradition and a technique that is still used today. Also, the vegetable okra is used as a thickening agent and plantain has commonplace in many traditional Brazilian dishes. Using dry smoked dish and prawns as well as adding chili peppers, coconut milk and ginger to dishes is also thanks to the African slaves.

Dishes that have a significant influence on the Africans are acarajé (fried black-eyed pea fritter), Moqueca (fish stew made with coconut milk), vatapá (a coconut and prawn stew), and caruru (okra, peanut, and shrimp stew).

The impact of Africans in Brazil impacted its culture which is incredibly significant today and seen through the spirit of Samba, the complexity of capoeira and the belief system of candomblé.

As Brazil began to expand coffee exportation and began to compete with Cuba on sugar cane cultivation, sugar exports declined. It was around this time when gold was discovered which created a huge influx of Europeans to try their luck at fortune.

Sugar supply was high in demand and African slaves were imported to manage and work on the sugar cane plantations. Just as sugar exports started to decline towards the end of the 1600s and in 1690, gold was then discovered.

Credit: Sebastião Salgado

Gold mine of Serra Pelada, State of Pará, Brazil, 1986 (www.independent.co.uk)

The gold rush of the 1700s in Brazil brought on an influx of Europeans trying their luck at fortune on the fields. African slavery continued throughout this period until 29th August, 1825 at the Treaty of Rio De Janeiro, which officially recognized Brazil as an independent country. The agreement between Portugal and Brazil eventuated to the cessation of the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1888.

The Japanese-Brazil agreement in the early 1900s brought the first Asian immigrants to the country. Subsidised by the government, the voyage of the Kasato Maru, a boat loaded with Japanese citizens, promised a life of opportunity and prosperity in Brazil. These Japanese immigrants became the country’s workers after the abolishment of African slaves in the sugar cane fields.

The Atlantic slave trade abolishment in 1888 impacted Brazil significantly culturally, socially, and economically. The labour gaps in Brazil encouraged immigrants from Europe and Asia to work as labourers and business owners in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

The Japanese-Brazil agreement in the early 1900s brought the first Asian immigrants to the country and to this day, there is a strong perception of ‘Asian Cuisine’ in Brazil. The Kasato Maru was a boatload of Japanese citizens who were promised a life of prosperity and opportunity and the voyage was subsidised by the government. On arrival, the Japanese immigrants, after the abolishment of African slavery in the sugar cane fields, became the country’s workers on the coffee plantations in Brazil. The labour gaps also encouraged Europeans to come and work in Brazil and begin new lives.

Sushi, Yakisoba (fried noodle dish), Pastel (deep fried filled pastry), and Esfiha (baked bread filled with meat, cheese, or spinach), are some dishes found in Brazil as a result of Asian immigration in the 20th Century.

The Regional Differences of Brazilian Cuisine

Due to the vast size of Brazil, the five main regions within it have distinct and varied climates, cultures, people and cuisines that can be summarised in the following:

North Brazil

The northern region of Brazil is an area of wild surroundings and due to it being fairly remote, the cuisine found in the states of the north is strong in Indigenous and African influences. This region was discovered later when the Tupi people roamed the land. With the vast water resources in the north, there are over 1200 fish species that can be found, among these is the Tambaqui fish which is either salted, smoked, or dried. The notable culinary regions of the North are Amazonas, Pará, Maranhão, and Rondônia.

Significant North Brazilian Dishes

Pato no tucupi (duck in Tucupi sauce) from Pará is a dish where the duck is marinated in lemon juice, oil, and garlic, then boiled in a sauce which is made from the fermented extract of cassava (tucupi).

Tacacá is a soup made from a tucupi broth, Jambu leaves, garlic, and onion which is poured over tapioca pearls, chicken, and prawns.

Maniçoba is a rich stew of beef, manioc leaves, herbs, garlic, and onions and cooked for a long period of time in a clay pot.

The Regions of Brazil @mapsof.net

North East Brazil

North Eastern Brazil was abundant in sugarcane plantations from around the 1500s and the area was heavily populated with African slaves that have influenced the cuisine and culture. Some examples of a strong African influence in dishes within the North Eastern region are the regular use of coconut milk, okra and dendê (palm oil).

The cuisine of all the nine states encompassing North Eastern Brazil reflect the abundant ingredients found in this region, in particular, spices, seafood and fruit. All regions of the North East - Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas, Bahia and Sergipe produce a variety of culinary delights.

Acaraje (www.gastronomiatupiniquim.blogspot.com)

Significant Northeast Dishes

Acarajé

It is a dense and delicious fritter that is made with black-eyed fritters, it is then filled with shrimp and Vatapá.

Moqueqa

Is a seafood stew that has two variations in this region.

One is from Pernambuco (coconut milk, palm oil, tomatoes), as well as Bahia (coconut milk, ginger, coriander).

Carne de Sol

Is a delightful salted beef that is dried in the sun for 1-2 days. It reflects simple preservation techniques used by the native Brazilians. The use of this meat is versatile and can be grilled fried or baked.

Central West Brazil

This region’s cuisine remained off limits from immigrant influences and is strong in indigenous tradition. It was not until the 1950s that the area became popular when Brasilia, the new capital of the country had been built.

The regions in Central West Brazil are Mato Grosso, Goiás, and Mato Grosso do Sul

and the dishes found within them use a lot of fish, dreid meat, plantains, corn and cassava.

Central West Dishes

Arroz com Pequi

Is a rice dish that contains onion, garlic, chicken broth and Pequi. Pequi is a firm orange fruit that is treated as a vegetable due to its cheesy, ‘barnyard’ like flavours. It contains spikes on its inner core so must be eaten with caution.

Pintado na Telha

A fish dish that is baked in a claypot containing a Pintado fish, lemon, garlic, green onions and tomatoes.

Farofa com Banana

Farofa is a side dish consisting of fried cassava flour. In farofa com banana, plantains are added as well as onions herbs and butter.

South East Brazil

South East Brazil is the culinary hub of Brazil and its cuisine is a reflection of the many immigration movements in the late 19th Century. Indigenous traditions, Asian and European ingredients and techniques contribute to the wide variety of dishes found the four states of this region; Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais.

South East Dishes

Feijoada

The dish Feijoada is considered the national dish of Brazil. A slow-cooked stew containing black beans, various cuts of pork, onions and herbs served with farofa, oranges, and greens.

Pão de queijo

This bread is only small and is a popular street food snack. It contains Minas Gerais cheese and cassava flour.

Bolinhos de Bacalao

This dish is a strong reflection of European influence containing Bacalao, a preserved salted cod mixed with potatoes, and herbs, rolled into small cylinder shapes that are then deep fried.

Feijoada (www.culturalpulse.com.au)

Southern Brazil

The south of Brazil experienced heavy immigration from Europeans and its cuisine is very meat-centric yet also contains balanced notes of the indigenous diet. Originally, Tainha fish was consumed widely by the natives, yet livestock became the focus in this region that is made of 3 states; Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, and Santa Catarina

Southern Dishes

Churrasco Gaucho

Is one of the most iconic cooking methods from Brazil. Borne from the Gaúcho (cowboy) culture, it is centered around different cuts of meat that are seasoned with salt or marinated in milk, cachaca, or cognac and roasted over an open fire.

Barreado

This is an intense beef stew made with onions, tomatoes, and garlic that is cooked in a clay pot that is sealed with flour and water ‘glue’ and cooked for many hours. It is then served with plantains and farofa.

Arroz de Carreteiro

A rice dish that is fried with rehydrated dried meat, onions, and garlic and then simmered in stock until cooked through.

Modern Brazilin Cuisine

Many native chefs in Brazil are unearthing traditional techniques and ingredients in their restaurants and bringing them to the forefront of the global culinary scene, with a focus on fresh and local produce. Among these chefs are Alex Atala (D.O.M), Helena Rizzo (Mani), and Rodrigo Oliveira (Mocotó), who are innovating the historical culinary landscape of Brazil while bringing awareness to sustainable and ethically sourced ingredients.

Brazilian Cuisine is a reflection of the country’s varied history and culture making it a fascinating culinary experience to explore. Due to its vast landscape and varied regions, the cuisine is diverse and contains some wonderfully unique dishes and ingredients like no other in the world. I have just touched the base of it in the words written above, and I am looking to share more of it in detail with you in the near future.

While you wait, feel free to try out some recipes that have been inspired by Brazil here.

Why Are Poppy Seeds Banned?

The poppy seed is such an undervalued culinary ingredient in many countries, and disappointingly, in some regions of the world, these earthy balls of crunchiness are even banned. The history of poppy seeds and the plant they are derived from have an extremely coloured history of medical breakthroughs, war, and addiction.

Where is the poppy seed plant from?

Poppy seeds are only found in the opium poppy plant, known as Papaver Somniferum which originated in Anatolia dating back around 5000 BC.

The first known cultivation of this plant and its uses as a ‘joy plant’ was recorded in 3500 BC in cuneiform clay by Sumerians, the world’s first civilization. There is also evidence of opium poppy remnants found in ancient sites in northwestern Europe and the Alps. The opium poppy plant and its uses ranged from a food source or spice to a sedative, and pain suppressant as well as used for spiritual and religious rituals.

The Greek botanist and physician, Pedanius Dioscórides, who served in the Roman army mentions the use of the opium plant in De Materia Medica, a collection of works that cite around 600 plants and natural medicinal properties that could be derived from them.

The seeds of the opium poppy plant are usually cleaned and processed before being sold as a culinary ingredient, yet they may still contain a slight opiate residue which can show up as positive in a drug test. Poppy seeds should be available for all to enjoy as they are rich in antioxidants and minerals as well as other benefits.

Opium poppy plant

What is Opium?

Opium is derived from the seed capsules of the opium poppy plant. It was first hand harvested by splitting the pod of the plant so the milky latex would seep out and dry. This dried liquid is then used as a base to make a variety of drugs and this was quite prevalent in the 1800s when it was used as a pain killer. The latex of opium contains around 12% morphine, codeine and other alkaloids.

The ancient societies of Greece and Egypt used opium as a sedative, pain reliever, anesthesia, and also recreationally. Opium became a highly sort after commodity that was traded in the 6th-7th Century BC by Arabs along the silk road, a network of trade routes connecting Europe, Asia, India, and China.

In the 1600s, tobacco smoking in China became popular and so too, did smoking opium which started a huge addiction for many throughout the country, causing a ban on the use and sale of it in the 16th Century. Despite the ban, opium and its uses still flourished.

Throughout the Western world, opium was used medicinally as a pain reliever and a cure for those afflicted by mental illness. Opium as a prescription began around the 1600s in the United States and it wasn’t until the late 1800’s that it was recognized as an addictive drug, despite its’ known recreational uses in the 14th Century.

The Opium War

An opium den @poppies.org

By the 1700s, the British East India Company began trading with China for tea, porcelain, and silk in return for British silver. This trade wasn’t extremely profitable so with their connections with opium growers in India, they began smuggling opium into China which was sold for silver, and that silver was then used to pay for the tea.

The addiction to opium in China grew rapidly and had detrimental side effects on the country’s economy and social structure. The Chinese government intended to put an end to this trade that was affecting their country by destroying and confiscating over 1,000 tons of opium being held in Canton by British merchants. This forceful action by the Chinese government was the onset of a series of events that would lead to the Opium War of 1839 and the subsequent second war in 1856.

China’s reputation as the largest economy in the 1820s was reduced by half by the end of the two wars, with the first war leading to the British having access to five major trading ports and control over Hong Kong. The second Opium war saw Britain and France join forces to legalise the trade of Opium.

Growth and consumption of opium were banned in China in the early 1900s which led to its decline in trade in less than 20 years. The use of opium spread through the United States during the gold rush of the mid-1800s when the Chinese worked to seek money. Smoking dens of the drug heightened fears of encouraging prostitution and the increase in crimes, this in turn issued a discriminatory ban on Chinese immigrants from 1882-1892.

Early trade conventions of the 1900s led to the complete ban on opium and China’s defeat of Japan in WWII was the beginning of the People’s Republic of China and the total eradication of opium in 1949.

Opium is still used today in the medical world in the form of morphine or codeine, both derived from opiates, yet used in a heavily regulated manner in the medical world. Heroin was developed in the 1870s as a milder alternative to morphine to relieve pain and it was also used as a cough suppressant. The use of heroin grew into addiction among many in the United States.

How did we end up here?

From poppy seeds to opium poppy plants, to war to heroin……

Believe it or not, I was inspired to create a recipe after this research using poppy seeds as a paste filling for a wonderful traditional Jewish pastry known as Hamantaschen.

A Short History of Ramen

Throughout Asia, noodle dishes are one of the most popular to eat and come in varying types of textures, ingredients used, serving, and cooking methods. While each country prides itself on a significant noodle dish, one of the most recognised types of noodles within both the region and internationally is ramen. Ramen is a humble dish of wheat noodles, broth, toppings and is synonymous with Japanese food and culture, developing over the years with the evolution of Japan.

The History of Ramen

Japan’s surrounding countries have strongly influenced its food culture starting from as early as 300BC. The Chinese have influenced a diet of rice and noodles within the Japanese culture and the introduction of Buddhism from Korea eventuated into a 1200 year ban on beef products, equipping the country to master the art of sushi and be world-renowned for its high-quality seafood.

The treaty of peace and amity in 1854 forced Japan to open its ports to American trade, ushering in a plethora of immigrants and foreign workers into the country. Yokohama, once a tiny fishing village, boomed because of the treaty and grew immensely with the rise of Industrialisation in 1868.

The first Chinese restaurant opened in Yokohama in 1870 and as Japan’s economy grew, many more Chinese students and workers migrated and spread around the country. Rairaiken , a restaurant in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, opened in 1910

In the Asakusa district of Tokyo, a restaurant run by Chinese workers opened in 1910 and served a dish called Shina Soba (Chinese Soba). This dish consisted of broth, noodles, pork, fishcake and nori, closely resembling ramen of what we know of today.

The word ramen relates to the actual noodles, transcribed into Japanese from the Chinese word ‘la mian’, meaning pulled noodle.

La mian noodles are from Lanzhou, made from wheat flour that is pulled, folded and stretched until the correct thickness is achieved.

Shina Soba / Credit: fukuokanow.com

What are the main ingredients in ramen?

Despite hiding behind a façade of a humble bowl of soupy noodles, the elements of ramen are complex, time-consuming and require extreme perfection to achieve a delicious, balanced dish. Those elements comprise broth, tare, noodles and toppings.

Broth

Traditionally ramen is made with a pork broth which requires many hours of simmering pork bones to extract collagen, fat and flavour. The combination of both pork and chicken broth is also popular and in modern style ramen, crab, prawn and lobster stock is also used.Tare

The flavour of ramen can be credited to tare, the seasoning element of the broth containing glutamate through umami rich foods or the addition of monosodium glutamate. Dashi, made with kombu (kelp), katsuboshi (smoked and dried bonito flakes) OR niboshi (anchovy), is also used in the tare to add a full-flavoured layer of umami.Shio (salt), Shoyu (soy sauce) and Miso (fermented bean paste) are the building blocks on which the three types of tare is built. Other ingredients can be simmered with these base flavours such as sake, ginger, mirin, vinegar, garlic or green onions. Shio tare results in a clean and pure taste, Shoyu adds sweetness and colour while miso provides an earthy taste with an opaque appearance.

Noodles

Ramen noodles come in a variety of textures and shapes and are made simply from wheat flour, salt, water and alkalized mineral water also known as kansui. Kansui is the essential ingredient in the noodle allowing them to have a bouncy texture and egg-like flavour. The colour and texture depends on how much kansui has been added to the dough and the noodles can be flat, wavy, curly, thick or thin.Toppings

Toppings of ramen vary and can include chashu (grilled braised pork belly), ajitsuke tamago (marinated egg), Naruto (fish cakes), Nori (seaweed paper), bean sprouts, corn, menma (fermented bamboo shoots), black fungus, corn, spicy miso and many more.

Is ramen difficult to make?

The Japanese cuisine and culture is a very traditional and disciplined one. It takes many years to become a master at just one element let alone one dish.

I did, however, try to make a ramen from scratch, the result wasn’t too bad, but it was a lot of work.

Feel free to try it yourself and let me know how it went.

Quinoa - The Superfood of the Ancient and Modern world

A cluster of purple flowering, over metre-high quinoa, is truly a magnificent sight to see. The goosefoot plant is closely related to beetroot, spinach and amaranth with edible leaves but most importantly, a nutrient-enriched seed.

What is Quinoa?

Quinoa is now known today as one of the most popular ‘superfoods’ and is available around the world. This pseudo-cereal is extremely versatile eaten as a grain, ground into flour and also made into dairy-free milk. It is a gluten-free plant-based protein that contains amino acids, fibre, vitamins and magnesium.

This ancient crop has existed for over 7,000 years, finding its roots in the Andes region surrounding Lake Titicaca in Bolivia and Peru. Kinwa (in Quechuan language, used by indigenous Andean people) held strong cultural and religious significance within the Incan empire. It was a gift to the Gods and was known as “Chisaya Mama”, the mother of all grains.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas in the 14th Century, they burnt fields of quinoa, banishing the use of the seed for religious ceremonies.

Quinoa Fields

Credit: Cristobal Demarta via Getty Images

Fortunately, quinoa is an extremely stable and adaptable crop, surviving in harsh environmental conditions with little water needed. There are many types of quinoa that have adapted over the years to the varying geographical areas along the Andes, however, the most exported quinoa from South America is the large white seed which we see on our supermarket shelves.

Both Peru and Bolivia contribute to 80% of Quinoa’s global trade, with Peru being the largest producer of the two. Quinoa is grown in dry climates and the surge of its popularity and price after 2006 saw certain varietals starting to be cultivated around the world such as the United States, Europe, Africa and Asia.

The United Nations declared International Year of Quinoa in 2013 to raise awareness of this important ancient crop and to bring attention and support to the farmers in Bolivia and Peru. Quinoa from Bolivia is associated with the name Quinoa Real, produced by 60% of the farmers and certified organic. Peruvian quinoa is broken down into the categories of organic, biodiverse, and supporting women’s livelihoods.

The Andean grains program in South America focuses on aiding poor communities that farm quinoa, in particular women who are the majority farmers of this popular seed. Due to the fact that only certain varieties are exported, the Andean Grains Program are focusing on indigenous strains and implementing them into a local school and hospital diet programs to ensure their long term survival.

Quinoa grows in dry cool climates and begins as an extremely leafy yet slow-growing plant. Sprouting to over a metre high, the quinoa plant begins to flower and most of the leaves fall off. It is at this point the seeds are ready to be harvested.

The stalks are cut and arranged in bundles that are interwoven to withstand strong winds in a formation known as “chujilla” (huts) which are then left to dry. Harvesting in South America is mainly done by hand and when the plants are dry enough, the seeds and seed heads are rubbed gently so the two separate.

The seed is coated in a saponin which is a natural protectant from insects and birds, however, it is extremely bitter. This coating is rinsed and polished away revealing the wonderful grain which we recognize as quinoa.

Quinoa is extremely versatile in cooking due to its texture and neutral flavour. You can create wonderful salads, risottos, porridges and even desserts that are vegan, gluten-free and high in protein.

I made some quinoa fish cakes with a mango chilli dressing if you want to try the recipe HERE

What is Couscous?

With North African origins of about 2000 years ago, couscous has spread around the world – not so much in many forms but in many dishes. In Berber, the word couscous means well-formed or well-rolled and it is an ingredient that has religious and spiritual significance. It is cooked at family celebrations such as weddings and is also eaten at the end of Ramadan. Its nutritional profile is minimal in protein and fibre, like pasta.

How is Couscous made?

Couscous is made from the product of wheat milling known as semolina (not flour) which is crushed into small granules. It is an ingredient that is extremely versatile, quick, and easy to cook and used in both sweet and savoury dishes. Although couscous is made most commonly from wheat, it is also found using millet, corn, sorghum, and barley.

Israeli couscous or ptitim is larger than the traditional type by using both semolina and regular flour, it has a chewier consistency and bite to it.

Traditionally, couscous would be handmade on a large flat plate where semolina is sprinkled lightly with salted water and plain flour. The mixture is rolled until the granules appear and are then sieved with dry flour to separate and obtain pellets of a similar size. This laborious process is repeated, and the couscous is then dried in the sun, stored, or cooked.

Couscous around the world

Couscous in Morocco is usually steamed to be cooked in special pots known as a couscoussiers where stock or stews can be made in the bottom vessel while the couscous is steamed on top, allowing it to maintain a light and fluffy texture. It can also be mixed with water and oil before steaming and then intermittently stirred over a period of time adding butter until the grains are fluffy and cooked. These days, instant couscous is conveniently available, and all is needed to cook it is right parts stock to granule, and an 8 – 10-minute wait.

Preparing Couscous in Morrocco’s Hight Atlas Mountains

Credit: JEff Kohler /NPR