explore the world through the universal language of food

Cassava, the resilient crop

Cassava (yuca, medico, tapioca, manioc) is a starchy and tuberous root originating in the Americas.

It is the sixth most important crop in the world, feeding around 8000 million people a year. This hardy vegetable is a globally traded commodity with a deep history, long-withstanding versatility and a hopeful, sustainable future.

Origins and Early Domestication

This perennial shrub originated in the New World somewhere along the southwest border of the Amazon Basin between Southern Brazil and Eastern Bolivia. Its domesticated variety was discovered in the 19th Century and this particular varietal is estimated to be around 8000-10000 years old. It is one of the oldest cultivated crops that spread quickly throughout Central and South America and was eventually dispersed to Asia and Africa.

Cassava has been a significant crop of survival and symbolism for the Indigenous people of the Americas. For the Maukshi tribes of Guyana and Northeastern Brazil, it was a resilient food before, during and after colonisation and appeared in mythology and religious ceremonies. The Mayan civilisation was also responsible for the cultivation of cassava as well as its spread throughout the Americas.

The indigenous peoples learned how to prepare cassava (through trial and error and I expect possibly death), in a way that would reduce the toxicity of this nutritionally dense crop.

Unpeeled Cassava

Two common methods used to prepare cassava were to grate and strain the moisture and then allow it to dry and grind it into flour (farina), the second method is to peel, wash and boil it. The liquid from the cassava, once removed from the starch, can also be used after it has been fermented and then boiled for several days. This is known as tucupi, a unique product used in Brazilian dishes such as pato no tucupi (duck in tucupi) and tacapa (soup).

With a deep root system, the cassava crop is extremely resilient in adverse weather conditions and was integrated with other crops such as maize and beans.

In pre-Colombian times, cassava was an important commodity that was traded throughout the coastal and highland regions with other products cacao and maize. It was also used in various rituals and community gatherings.

The Colombian Exchange, a significant trade route established after Christopher Columbus voyaged to the New World in the late 1400s, moved cassava and other plants, diseases, cultures, and ideas from the Americas to Africa and eventually to the Old World.

Cassava in world cuisines

This diverse and multiple-use crop can be found in an abundance of dishes significant to cuisines around the world.

SOUTH AMERICA

Farofa, is a toasted cassava flour with butter, onions, sometimes bacon and spices. It serves as a side dish to grilled meats and theBraziliann favourite, feijoada, Pao de quejo, a sticky and cheesy snack is also made with cassava flour.

In Peru, cassava is often boiled, then fried until crispy as a side dish or on special occasions, is served in Juane, a type of Amazonian tamale that consists of rice, meat, spices, beans and eggs, blanketed in a bijao leaf and steamed for several hours.

Apart from making crispy cassava fries, Enyucado, a popular Colombian cake is the perfect bake to showcase this wonderful ingredient.

Casabe, is a bread made only from cassava is found in Colombia, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. The cassava is grated, dried and cooked until it forms together then served as a side dish or as a base for stews and sauces to be piled on top.

In Colombia, cassava is grated and made into a sweet cake called Enyucado

AFRICA

Fufu, a sticky dough in Nigeria consists of fermented cassava only, whereas in other Western African countries it is pounded with plantains and cocoyams. It is

Cassava flour in East Africa is used to thicken stews and the leaves of this crop is often included into stews and soups with coconut milk, vegetables and meat.

ASIA

In Asia, cassava can be seen in many sweet dishes and drinks like bubble tea, tapioca pudding with coconut milk and mango and getuk in Indonesia, a sticky sweet dessert that consists of palm sugar and cassava showered in grated fresh coconut. It is included in Meen curry in India and commonly sliced thinly and fried into crisps that are sprinkled with salt and chilli.

The cassava crop has fed civilisations for centuries and has withstood dramatic climate changes, its resilience has allowed it to be adaptable and to flourish in any continent around the world. Not only is it used in the culinary world, but it’s also industrial applications have made it an extremely sustainable resource, used for packaging, cosmetics and biofuel.

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Sopes - an Aztec Snack

Honestly, I had only tried sopes after living in Mexico for around 4 months and once I did, the world upon my palate changed.

It’s not a common street food, or so I thought, but I guess I was just not looking for them. I went to Cuernavaca for the weekend to spend it with my friend and his family to attend my first Mexican wedding which was quite the party and experience. The journey from Mexico City was not a long one, but a restless one so I had quite a long sleep and when I woke up and stepped into the kitchen, I sleepily saw a a glorious sope production line happening before my eyes.

My friend’s family had all come together from all corners of the world, and his mother was busy in the kitchen preparing food for 4 hungry boys, their partners and children. Not only was she making a mountain of sopes, but there was also a large bubbling pot of pozole to go along with them, needless to say, both were delicious, and I even enjoyed the tripe in the pozole (a traditional pork-based soup).

The sopes came together quickly and in all their simplicity they were unbelievably delicious, topped with straightforward and flavourful beans, cheese, queso fresco and hot sauce.

Sopes with black beans, avocado, cheese and hot sauce

One cannot talk about sopes without talking about maize and nixtamilsation. The maize crop was a fundamental element in Aztec societies and remains at the forefront of Mexican cuisine today. Even before colonisation, maize was processed by a method known as nixtamalisation. Treating the corn with alkaline solution (lime water), not only gave it a unique taste, but it also enhanced the nutritional content of the maize (specifically niacin), which was key to preventing pellagra.

Masa Harina is the dried flour of nixtamalised corn is the glorious ingredient that can be made from a myriad of corn types which can be transformed into cakes, tortillas, gorditas, tamales, champurrado and also, of course, sopes.

What Are Sopes??

Sopes are a much thicker version of a tortilla and are reasonably small in size (5-10cm), they have a ‘lip’ to hold ingredients that are layered on top of them, which range from beans, shredded pork, chicken, cheese, avocado, herbs and hot sauce.

They are not as common as tacos on the streets of Mexico, however, they are a more robust and portable snack, and just as delicious.

Masa harina (dough flour) is the base of sopes, which then has water added to it to create the dough. The dough is pressed, dry-fried, shaped and fried. There is no need to add salt or herbs to sopes. As simple as the base may seem, the process of nixtamilsation gives the corn an earthy and slightly tangy flavour profile.

The basis of sopes is essentially the same, however throughout the various regions of Mexico, everyone adds a variety of different toppings that reflect the colourful culinary diversity of the country.

Travel to Mexico city (De Effe), and you will find sopes piled high with papas con chorizo, potatoes and soft, slightly spicy Mexican chorizo. When you head south to Oaxaca, the culinary treasure of the country, sopes or memelas are showered with queso de oaxaca and sometimes crispy chapulines (grasshoppers). Jalisco’s sopes are earthy and deeply flavourful with slow-cooked meat stews such as birria. In Yucatan, sopes are brighter in flavour, yet robust with famous pork dishes such as cochinita pibil.

If you do travel to Mexico, make sure you try this wonderful dish that is robust, flavourful, and you can never ever stop at just one!!

If you can get your hands upon some good masa harina you can always try your hand at making sopes at home…. I made mine with black beans, avocado and cheese.

Cochinita Pibil

Credit @meridadeyucatan

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Ajiaco - Colombian Chicken Soup.

As I sat in a small restaurant in Bogota, I looked around at the homely interior, strong wooden furniture, slightly kitsch decorations, and a proud Colombian flag hanging over the ‘bar’. All the tables overlooked the live entertainment; a small cobblestone sidewalk filled with an occasional tourist, carts selling cocadas, and vendors selling small handicrafts.

The simplicity of Colombia, its beautiful landscape, her coloured yet troubled history, and straightforward food all encompass a unique experience to anyone passing through, or staying a while….

A rather plump older lady places a heavy terracotta bowl of stew (slash) soup in front of me with two hands, then a plate of rice with an extremely buttery sliced avocado. I dipped the large spoon into the soup and tasted it. There was warmth and comfort in this thick flavourful broth that was creamy with just enough acidity – although the flavour combination was rather foreign to me, it felt somehow familiar and remains to this day one of my favourite Colombian dishes I have ever tasted.

The very name of this soup, Ajiaco, includes the word Aji, meaning chilli pepper, in the language of the Taino people. Taino were Indigenous inhabitants that migrated from the north coast of South America and spread throughout the Caribbean, they were the most predominant society in the region before European contact in the late 15th Century.

The Taino people lived in a hierarchical society that crafted tools, boats and ornaments, worshipped deities of natural elements such as Yucahu the god of cassava and the sea, and ate an abundant diet of seafood, cassava, beans, maize, peppers, wild plants and hunted meat.

Ajiaco is a traditional soup that has evolved with the history and culinary landscape of Colombia. More than a soup, it is a stew consisting of filling ingredients that is perfect for cooler seasons and is accompanied by a variety of sides making it a very substantial meal.

The most popular Ajiaco is found in Bogota, and is known as Ajiaco Santafereño. The main ingredients in this Ajiaco are chicken on the bone to extract the hearty collagen and fat, three types of potatoes (criollas/yellow, sabaneras/red, pastusas/white), guascas, an extremely aromatic Colombian herb, corn on the cob, cream, capers and avocado.

Travel around Colombia and you will find variations of Ajiaco – in the Cauca Valley, the dish is extremely herbaceous, using a variety of plants from the region, in the north, along the Caribbean coast, you will find coconut milk in the dish which gives it a milder taste, whereas in the mountainous region of Antioquia, it is hearty and filled with many root vegetables.

The unique ingredients found in Colombian Ajiaco - Guasca and three types of Colombian potatoes

Guasca

Credit @amigofoods

Saberna, Criolla and Pastusa Potatoes of Colombia

Credit @ATouchofRoJo

Ajiaco, although most recognised to be a Colombian dish, can be found with slight variations in Cuba, Venezuela and Peru.

Ajiaco Cubano is robust and complete containing many root vegetables such as cassava, malanga, sweet potatoes, potatoes and different meats like beef, chicken, pork and chorizo. The heavier spiced flavour is a result of the addition of cumin, oregano, bay leaves, and paprika and it is full of plantains, tomatoes, corn, garlic, onion, coriander and peppers (capsicums).

Venezuelan ajiaco contains beef and pork and more vegetables and fruit such as carrots, plantains, corn, and tomatoes, and is flavoured with coriander, garlic, onions, cumin and oregano.

The significant difference of Peruvian Ajiaco to its Colombian counterpart Is the addition of huacatay (black mint), coriander and aji Amarillo (yellow chilli).

Whether you try this dish in Columbia, Cuba, Venezuela or Peru, Ajiaco is a humble stew that reflects the tradition of the indigenous people, demonstrates the vast abundance of ingredients throughout Latin America and reflects history in every, delicious bite.

Every version of Ajiaco whether in Colombia, Cuba, Venezuela or Peru reflects a variety of significant ingredients to that country. A humble stew that tells tales tradition from the indigenous people, and a varied agricultural landscape and reflects history beautifully in an extremely delicious way.

SOME MORE FOOD HISTORY….

Gula Melaka

Gula Melaka is a rich, caramel-like, unrefined sugar derived from the palm tree. It is named after the Malaysian state, Melaka, and is a common ingredient found in Southeast Asian dishes, in particular, sweets and desserts.

How is it made?

Made from the sap of the flower buds of the coconut palm, the first process of making gula Melaka is to tap the flower buds, making a small incision in the flower stalk, the sap is drained and collected. This sweet, unrefined liquid is also known as Neera, which is collected once or twice a day and cannot be kept unattended for some time as it is highly susceptible to fermentation. The Indigenous tribes that used to collect this sap learned that heating it to allow the water content to evaporate found longevity in this sweet and natural product. This process is a significant and lengthy process for the result of Gula Melaka, taking up to 7 hours. When the sap becomes a dark–syrupy colour and consistency, it is then poured into molds, traditionally bamboo or coconut shells are used for this. The syrup hardens, resulting in a firm, sweet block of Gula Melaka.

Gula Melaka travels the world

Gula Melaka accompanied spices and textiles from Southeast Asia through to India, China and beyond. Europe via trade routes. The most important was the Maritime Silk Roads that extended 15,000 km connecting the East to the West. They stretched from the western coastal areas of Japan to the Indonesian islands, around India and into the Middle East, and eventually the Mediterranean and Europe. Significant ports in Southeast Asia around the 15th and 16th Century were Malacca, Aceh, and Java. The European colonisation in the 16th Century, notably the British, Portuguese, and Dutch, also was a significant catalyst for moving this specialty sweet gold, gula Melaka, from Southeast Asia to Europe.

The dark, caramel taste and texture of pure Gula Melaka, make it a versatile ingredient that can be added to traditional cakes and desserts such as kueh, cendol, ondeh ondeh and sago puddings. It adds depth to sambals, sauces, and marinades.

A simple but pure ingredient that is steeped in tradition, brings together community and unique flavours for celebratory dishes, everyday enjoyment and sweet indulgence.

Hello

SOME SWEET RECIPES…..

Congee Around Asia

My memory was jogged today as I positioned myself in front of the laptop to write about the time I sat and savoured a bowl of Cháo Sườn (pork rib rice porridge), on a small plastic stool by the busy roadside in the Old Quarter, Hanoi.

A simple pot of rice porridge was being stirred over coals by an old Aunt and as she stirred the simmering rice, glimpses of pork emerged to the surface. She scooped a good ladle or two of it into a plastic bowl, covering the freshly cracked egg, and then topped it with scissor-cut fried dough sticks (quẩy) and a generous helping of pork floss (ruốc)

The honking symphony of the scooters, the footsteps of tourists and the chatter of the Vietnamese vendors around the street stall was a simple and raw setting, just as street food should be enjoyed. I found stillness and comfort in eating this centuries-old dish that has been made in a multitude of households and countries since its first documented recordings during the Zhou Dynasty (1000BC).

‘Congee’ is a derivative of the Tamil word ‘Kanji’ that was since changed by the Portuguese and came full circle to be known as Zhou/Congee. It is one of the simplest dishes you will find on your travels throughout Asia, yet every person who cooks it in every country puts their spin on flavours, and textures from lugaw arroz caldo in the Philippines, bor bor in Cambodia, kanji in India, or chok/jok in Thailand.

What is Congee?

Congee is a savoury rice porridge that is made by boiling rice in water or bone broth until the grains are completely softened and can still either be recognised, or they have been cooked down to resemble a type of white gruel. In some parts of Asia, it is also made with other grains such as millet, sorghum and barley. Congee is a dish that has been used to feed those in famine or settle an upset stomach and can be eaten at any time of the day. In Asia, rice porridge is popular for breakfast and can also be eaten as a side dish. The texture and individuality of a congee or rice porridge are in the base broth, type of rice/grain used, meat, toppings and finishing sauces and herbs.

China

Congee in China varies from region to region due to the availability of grains and ingredients. Cantonese congee in Guangzhou uses white rice and is decorated with century egg, beef, fish, or salted pork and peanuts with white pepper and soy sauce. Teochew porridge is light, and the rice grains remain separated and is served alongside small cooked and pickled side dishes of meat and vegetables. Hakka rice congee combines glutinous rice with white rice and contains heavier flavoured proteins such as pork belly and dried cuttlefish. The congee of Shanghai combines both rice and grains (usually millet), and is eaten with preserved vegetables, shredded tofu skin, and pork.

A significant type of congee is Laba, which is a traditional congee eaten on the eighth day of the twelfth month in the Chinese calendar and contains grains, beans, nuts, and fruit.

Laba Congee

Credit: Omnivore’s Cookbook

Cambodia

Cambodian borbor is more of a rice soup than a porridge where the grains of rice, usually Jasmine, swim around the bowl separately to take on the flavour of the stock which is commonly made from either pork or chicken.

The umami broth is sometimes boosted by dried preserved seafood and a pinch of MSG.

Borbor can be topped with shredded Khmer chicken (link to Khmer chicken), pork or even fish. It is optionally served with cha kway (fried dough sticks) and all the typical Cambodian condiments which adorn each table of any eatery (lime, fermented soy beans, pickled fresh chillies, red chilli sauce). Pair bor bor with an iced local coffee and you are set for the rest of the day.

Learn a little bit more about Cambodian bor bor HERE.

Nanakusa Gayu (7 herbs rice porridge)

Credit @justonecookbook

Japan

Japanese Okayu is a rather thick rice porridge that is usually made with polished short-grain white rice or sushi rice known as hakumai. The Japanese have used okayu for feeding babies, the elderly and also individuals with digestion issues. Some ingredients such as roe, salmon, umeboshi or egg can be added to okayu and the both is sometimes flavoured with dashi or miso. Influenced by the Southern Chinese tradition of preparing soup with 7 vegetables on the 1st Chinese calendar month, the Nanakusa no sekku (festival of the seven herbs), uses seven herbs in the Okayu and is known as Nanakusa-gayu.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s bubur ayam is a congee that takes your palate on a journey of flavours and textures. It breaks the mould of traditional rice porridge and is an extremely popular street food throughout Indonesia, particularly for breakfast. Each region in Indonesia has its own variations, but it is essentially a strongly flavoured chicken rice porridge. Shredded chicken is added, along with a myriad of textures and tastes such as roasted peanuts, fried scallions, green onions, cakwe (fried dough sticks), kerupuk (crackers), soy sauce, sesame oil and sometimes fish sauce. . It is not known as a spicy dish, however, there is always a little bit of sambal that is served on the side.

Thailand

Thailand’s Chok/Jok is an extremely smooth porridge that uses broken Jasmine rice and typically uses either pork (jok moo) or chicken (jok gai) to flavour it. The rice is cooked with water until an oatmeal consistency and gathers flavour, texture and colour from ingredients of pork meatballs and offal or chicken, soft-boiled egg, fried garlic, thinly sliced ginger, spring onions, a dash of soy sauce and a dusting of white pepper.

Philippines

Lugaw is the umbrella term for the Phillipino version of rice porridge which can be savoury or sweet and use a variety of meats such as chicken, beef, pork fish and frog. The sweeter versions of lugaw contain chocolate (champurrado) or corn (ginataaing mais).

Lugaw arroz caldo is the chicken version that uses sticky rice to make the porridge. The rice is seared in oil with the rice, ginger, garlic and onion and then brought to a simmering boil until the grains have broken down into a soupy texture. Arroz caldo is tinctured with a saffron like colour that is imparted by kasubha (dried safflower).

The extremely savoury, meaty arroz caldo is topped with fried garlic, boiled eggs, spring onions, a splash of fish sauce and a generous squeeze of calamansi.

Chicken Arroz Caldo (Philippines)

Credit @panlasangpinoy

Chok/Jok from (Thailand)

Paal Kanji (India)

Credit @yummytummyaarthi

India

In the vast country of India, many types of Kanji or rice porridges use a variety of rice and including lentils or beans. Other ingredients used in Indian kanji include milk, curd, and coconut as well as a finishing touch of tempered herbs, spices or chillies. A rice porridge known as khichdi is a mixture of rice and moong dal and has been used as a prescription food for centuries in Ayurvedic medicine.

Vietnam

Vietnam’s Cháo is extremely simple, yet one of my favourite rice porridge dishes in the region and comes in many varieties. It is cooked predominately with short-grain rice and water until it is a medium-thick consistency where the grains have completely broken down. Chao can contain pork offal, duck, mushroom, pork meatballs and mushrooms. It is dressed with meat floss to give an airy and chewy texture, partially cooked egg, green onions, crispy garlic, century egg, and soy sauce.

It is essential to pair it with quay (fried dough) to dip and wipe every last morsel of this tasty dish that is served not only for breakfast but throughout the entire day for sustenance and absolute pleasure.

The history of congee is extensive and its popularity in so many countries that have adopted this simple and humble dish and made it their own is a testament that it is one of the ultimate comfort foods that can make you feel better and transport you to a place of happiness and content in both your belly and your tastebuds.

Wherever you travel in Asia, make sure you seek out a bowl of congee, and if you aren’t travelling anytime soon, you can always make this simple fish congee recipe using Hong Spices white pepper seasoning.

Hello, World!

Cháo Sườn in Hanoi

Simply Delicious Cacio e Pepe

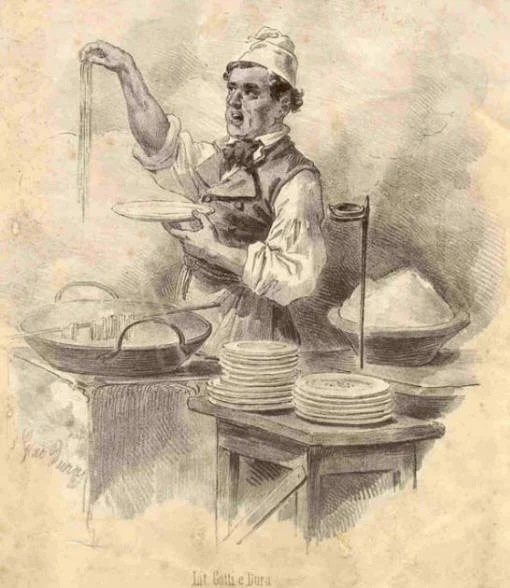

A tangled shiny tower of long tonnarelli strands, embraced in a thin yet visible coating of sauce is placed down in front of me right next to my glass of Montepulciano.

I look down at the simplicity of this dish and a rush of sheer giddiness overcomes me, I look around and smile triumphantly to myself, and plunge my fork into the glorious mess. Catching a few strands of the long rectangular spaghetti and twirling it around my fork (no spoons here!), I bite into the perfectly cooked pasta and savour the salty cheese sauce that is speckled with heat from toasted black pepper.

As simple as it appears to be, there is a whole lot that can go wrong with this traditional Roman dish, but when it is executed beautifully, it instils a lifelong memory that you can store forever in your palate’s flavour bank.

Cacio e Pepe. How can such a simple dish of cheese, pasta, and pepper be so memorable and popular, being served in its true form and thousands of other variations all around the world? Good food doesn’t have to be complicated and can be accessible to everyone.

There is a wonderful story of shepherds in the Apennine Mountains carrying dried pasta for a filling meal and pepper to help stimulate and warm them in the winter months. With the addition of cheese made from the milk of the sheep they were herding, the infamous cacio e pepe was invented.

It is more likely this Roman peasant dish was one of sustenance for the factory and mine workers on the outskirts of the Lazio region. Although pasta has been around in Italy since the 1300s, it was not an accessible food source as it is today. Prior to the 1800s, the lower class was more likely to have consumed bread and polenta while the elite societies enjoyed pasta. Rather than a vessel carrying delicious cheese and sauces, pasta was usually overcooked nestled amongst meat, vegetables, spices, herbs, and even fruit.

Cacio e Pepe was probably invented around the 1800s post-unification of Italy when pasta became a popular staple amongst the majority. The popularity of pasta most likely started in Sicily and Naples where wheat was sold relatively cheaply and it eventually spread throughout other regions of the country when meat became extremely scarce. Pasta then was industrialised during the 17th century when the torchio machine was invented, enabling pasta to be made in larger quantities.

Over the years the dish has morphed into many variations that even use Parmigiano Reggiano, resulting in a sweeter and nutty finish. Cacio e pepe has become an inspiration for many dishes such as ice cream, biscuits, pizza, and also risotto.

The Anatomy of Cacio e Pepe

Pasta

The pasta, tonnarelli or spaghetti alla chittara, is cooked in salty boiling water until springy and al dente.

Cheese

Cacio, meaning cheese is what brings a unique flavour to this Roman dish. Pecorino Romano, a sharp-tasting salty cheese made from 100% sheep milk is finely grated and mixed with a small amount of starchy pasta water until it has emulsified and made a ‘sauce’.

Pepper

The pasta is added to the ‘sauce’ and tossed a final time with toasted crushed black pepper, adding both warmth and spice to finish off the dish.

And that is all there is to it. simple, right?

If you haven’t tried Cacio e Pepe, I implore you to give it a shot and see how it tastes, serve it with a simple salad and a glass of your favourite white or red. It is one of the most comforting and simple dishes that has ever been invented and is truly one of my ultimate comfort foods (among others).

Try this delicious version of cacio e pepe here at An Italian in My Kitchen

Credit: An Italian in my kitchen

Or have some fun with these cacio e pepe crackers

A Short History of Cumin

As I was making my Sunday rounds at the markets, I spotted a beautiful bunch of baby carrots and immediately I just wanted them to roll around in a warm bath of salted butter, cumin, and a titch of honey. So that’s just what I did.

Cumin is not only my favourite spice, but also a historically important one that has been used for thousands of years. Despite some articles you may have read, cumin, the brown little wormy-looking seeds, which are readily available in markets and supermarkets, is not the same spice used in the mummification process of ancient Egypt. This type of cumin is known as Nigella Sativa or black cumin and has nothing to do with the brown cumin that is common in Latin, Indian, and Middle Eastern cuisines.

From feasts in northern Iraq around the 9th Century to Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, cumin has been documented to be used widely as a flavouring and natural medicine to cure or ease a variety of ailments such as digestive problems. From its origins in Mesopotamia, cumin moved through Europe as a spice, a medicine, and even as a currency in Medieval England where it was used to pay rent.

The Colombian Exchange, instigated by Italian Explorer Christopher Columbus began in the late 15th Century and initiated the transference of many food products from the old world to the new and vice versa. Animals, plants, cotton, sugar, and spices were some of the products that were traded along this route, cumin was one of them that made the voyage and embedded itself into a variety of cuisines in the Americas.

Despite being known as a spice, the cumin seed is actually a fruit derived from a small flowering plant technically known as Cuminum cyminum and is from the same family of dill, parsley, and carrot (no wonder they go so well together!).

The ‘roasty’ flavour of cumin has a slightly citrus tang on the tongue combined with warmth like cinnamon and invites complimentary spices like coriander, chilli, and turmeric. It is commonly used in savoury dishes but adds a wonderful layer of flavour to sweet dishes as well.

It is a small but powerful seed that helps stimulate digestive enzymes, aids the body in absorbing minerals, and is also known as an anti-inflammatory. Hot cumin water with a dash of honey is a wonderful way to start the day. It is also an element of modern-day pharmaceuticals and is used in aromatherapy.

From Mexico to India, Greece, and Turkey, cumin is one of the most widely used spices in cuisines around the world and adds a unique profile to any dish whether it be a soup, tagine, salad, or even tea!

Cumin is predominately grown in India, providing 70% of the seed to the world, however, it is also cultivated in North Africa, Turkey, the Mediterranean, Mexico, and the Middle East.

Cumin was and still is an extremely important commodity that can be grown in arid to semi-arid terrain, which allows it to be subject to sustainable agricultural practices. It is, however, an extremely labour-intensive crop that is usually hand harvested 120 days from when the seed is planted.

As with all ingredients put down before us, we should celebrate the history and the people who made it possible for us to be exposed to such diverse ingredients wherever we are in the world. Cumin, one of the first written recorded spices in the world is a special one and I encourage you to experiment with incorporating it in a recipe or two, enabling you to understand its wonderful flavour, warmth, and diversity.

Try experimenting with these main dishes….

The History of Food and Cuisine in North America

The Americas today is extremely diverse in culture, food, traditions, and cuisine. By exploring how and when humans migrated to the Americas and dissipated throughout the region, a beautiful pattern of ingredients spread across this vast expanse of land and then to the rest of the world.

From the nomadic communities who first travelled across the Bering Strait, to the Eastern Woodland People and the impact of the transatlantic slave trade, the land became dotted with a plethora of wonderful produce. Avocados, tomatoes, potatoes, allspice, black walnuts, and cacao are just a few of the ingredients we enjoy throughout the world. Every ingredient has a journey, every dish has a story, and here is a little introduction to the beginning history of food and cuisine in North America.

The New World is known as one of the last areas in the world to be inhabited by humans. People of Asiatic descent were originally thought to have travelled by land along the Bering Strait (the strait that links the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Sea) in the North. However, the latest anthropological research has revealed humans may have ventured out before this by boat, travelling along the Pacific shore of what is known as the Kelp Highway somewhere around 15,000-20,000 years ago.

Image as above from worldatlas.com

Originally, the people who first migrated to the Americas were isolated nomadic communities living off megafauna and native food plants. Through either climatic changes or human action, the extinction of around 60 megafauna species dramatically changed the diet and lifestyle of these once-hunter-gatherers. Most of their diets suddenly became reliant on agricultural means and they slowly cultivated and hybridised food crops that are found in every cuisine around the world.

Tribes were spread throughout the Americas, and strong communities and civilisations began to form at centralised trade routes. Canada, as we know it today, was covered in ice for some time and most probably was the last part of the Americas to be inhabited by humans.

The Eastern Woodlands People

The Eastern Woodlands People that settled in the North-Eastern part of America as well as those on the West Coast, formed communities that were sophisticated culturally, politically, and socially. Their diets consisted of wild game and many different plant species. Maple syrup was also discovered in this region and today is one of the most popular indigenous ingredients of America that is consumed worldwide.

Eastern Woodlands People. Credit - Unknown

The tribes that moved throughout North and South America were the Cahokia along the Mississippi River, the Incas in the Peruvian Andes, and the Aztecs in Tenochtitlan, Mexico. The varying locations of these tribes depicted the type of food they consumed whether it be seafood (turtles, fish, crustaceans), meat (bison, other game, possum, turkey), nuts, or berries.

One ancient planting system that provided staple ingredients to the Native American diet all year round was called the ‘Milpa’ or ‘Three Sisters’ crop. The trio of plants grown together provided an entire system of replenishing the soil with nitrogen, encouraging plant growth, allowing it to climb as well as providing shade for the soil, keeping it moist and a deterrent for weeds. The three sisters’ crop was found throughout the Americas and the use of corn, bean, and squash was significant to both the North and South American diets.

The ingredients available to the Native Americans were abundant and the fertile earth ensured a luscious, agriculturally forward, yet varied diet, even before European settlement. Native Americans made nutritionally complete dishes, cooking most ingredients by boiling or roasting over an open fire.

Ingredient Origins in the Americas

Below are some of the ingredients that originated in the various regions of the Americas. This produce spread throughout, ensuring a varied and palatable diet.

North America

Jerusalem artichoke, pumpkin, a variety of squash, beans (black turtle, navy pinto, cranberry), black raspberries, blueberries, cranberries, wild rice, black walnut, bison, sunflower seeds, turkey, maple syrup, pecans.

Cranberry Beans. Credit @gabriella.claire

Black Rasperries. Credit @Ulvi Safari

Central America and Mexico

Sweet potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, corn, allspice, avocados, chillies, bell peppers, and vanilla.

South America

Lima beans and other bean varietals, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, quinoa, cashew, peanuts, and cassava.

Potatoes. Credit @Markus Spiske

Tomatoes. Credit @Empreinte

Peanuts. Credit @me !

Corn was used extensively in many Native American dishes such as Sofkee (a dried corn porridge) and a simple version of Succotash (a corn and bean dish). The Native Americans ate well due to the wide variety of ingredients available in both the North and the South. A type of bread was made such as cornbread, cornbread with beans, and fry bread. Squash was used in stews and soups, as was fish that was roasted or fried. Cherokee fish and corn mush are dishes that still exist today, as well as altered versions of baked beans.

The indigenous Canadian diet included seal, whale, polar bear, buffalo, caribou, and vegetables. It was extremely high in calories to combat the freezing climate, and many ingredients were harvested, dried, and preserved to be eaten in the long winter months. Pemmican (dried meat and berries), maple syrup, and muktuk (dried whale blubber) were all consumed by the indigenous peoples.

The first Europeans in North America were Norsemen (Vikings) of Greenland, settling for a short period in Newfoundland, about 500 years before Christopher Columbus.

The arrival of the Europeans in the late 15th Century had a dramatic effect both on the native people of the Americas as well as on the environmental and culinary landscape. Crops and animals that were brought from the Old World thrived in the New World and vice versa. It was not only the transference of ingredients that changed American cuisine, it was also the people, commodities, and technology that contributed greatly to its evolution.

Soon after the arrival of Christoper Columbus in 1492, the Columbian Exchange was established. It was a global transference of plants, animals, people, technology, and disease between the Old World and the New World and not only impacted the countries directly involved but the whole world both positively and negatively. It changed the people, the landscape, and the climate of the Americas.

The Colombian Exchange. Credit @reconcilliationsofnations.com

Native crops of the Americas such as corn, tomatoes, cassava, potatoes, cacao, and chillies were important ingredients within the exchange and have become staples in many global cuisines of today.

Some of the European crops that were brought over from the Old World such as wheat, rice, spices, citrus, and bananas, thrived and redesigned many dishes and cuisines of the Natives. Unfortunately, with so much movement of crops, animals, and people between the old and new world, diseases were rife. The Native Americans had never been exposed to viruses or bacteria such as smallpox, typhus, measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, or cholera. The transference of these diseases was carried through humans and animals and as a result, rapidly diminished the Native American population by around 80-90 percent within the first 150 years.

The first Dutch colony of America was established in 1624. It was known as New Amsterdam which is the area where New York City sits today. Small parts of Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey were also included as part of the New Netherlands, however, it eventually was taken over by the British and became one of the 13 colonies. These British Colonies remained quite traditional in the dishes they cooked, which were typically either boiled or fried. The game was popular and used to make soups, stews, or even preserved or dried, animal fat was used for cooking and corn was an ingredient commonly used. Colonies close to the ocean enjoyed a diet rich in fish and Crustaceans.

New France, was the first colonisation of the French in North America and reflected traditional French fare with eh adaption of climate, availability of ingredients, the necessity to be resourceful, and the hardship of colonial life. As New France was eventually succeeded by British rule, the cuisine became heavily influenced by the English and Irish styles of cooking. Salt-cured meats, and seafood such as mussels, trout, salmon, lobsters, and eel were popular and abundant.

As the Native American population reduced dramatically due to the rapid spread of disease by the Europeans, the fertile expansive land of the New World required more labour for the agricultural industry to flourish. There was a growing need for workers to be placed on commodity plantations, in particular the sugar cane fields, an old-world crop that flourished in the fertile land of America.

Slave Trade

The Atlantic Slave Trade, the largest involuntary migration in history, was the importation of over twelve million African slaves to the New World from the 16th - 19th Century. Most slaves were sent to work in South America and the Caribbean, while only 5% were exported to North America. The slaves in North America worked mainly in the South as labourers on large plantations (cotton, rice, tobacco), small farms, domestic workers (cooks, servants, carers), and drivers.

The Slave Trade. Credit @thelibraryofcongress

Cooks of the household were on call every hour of every day, feeding the household, guests that would drop by, as well as the workers of the house and property. Southern Cuisine began in the kitchens of these enslaved Africans and has evolved to be a historically rich and significant cuisine in America.

Corn was used heavily used in Southern cooking and can be used to make a variety of dishes such as cornbread, grits, dumplings, and even alcohol. Small game meats and innards (chitterlings) were common as well as beef and pork. Other notable ingredients such as Okra, beans, cayenne peppers, and rice also reflected African cooking. Food was still cooked over open fires, or boiled and fried.

The cuisine of North America has evolved from simple British cooking and ingredients to an abundant culturally rich one, comprising of dishes that each have their place in time. Each dish or ingredient tells a story of immigration patterns, native food cultures, human adversity and the crossing of cultures from all over the world. The colonisation of America has also blended a variety of cooking techniques that still exist today including grilling meats over an open fire, spit-roasting and cooking root vegetables directly over ashes.

Achiote. Tales of the Lipstick Tree.

A cluster of small and hairy, rusty red heart-shaped fruits sit nestled amongst the branches of a 5-metre tree, waiting to pop open and reveal its vibrant flesh and seeds. The meaty part of this fruit is inedible, but the seeds have been used for centuries in many applications. This is achiote, also known as annatto, and has been used in cosmetics, as a textile dye for textiles, and as a natural additive to food for thousands of years. The beautiful colour and unique flavour of achiote has found its way into many dishes around the world.

The Origins of Achiote

Achiote stems from the Nahuatl word āchiotl and is formally known as Bixa Orellana. In the English-speaking world, it is also known as annatto, yet this is technically a name to describe the colour that is derived from the seed. Achiote finds its roots in Central and South America, with Peru, today producing the majority of the world’s supply.

Due to the complex genetic makeup of the plant, it is impossible to generate new strains, therefore there is only one type of achiote in the world, yet each can differ slightly depending on environmental circumstances.

Achiote History - from ancient civilisation to the rest of the world

Achiote was symbolically used in Mayan and Aztec ceremonies and rituals, representing blood, fertility, and the vibrancy of life. The seeds were also ground into a paste and added to a variety of dishes, creating a distinctive flavour and colour. When the seeds were soaked for a period of time, the liquid obtained a beautiful red which was then used to dye textiles. Other parts of the plant such as were also used as natural remedies to cure a variety of ailments such as inflammation or digestive disorders.

Intrigued by these wonderous plants, the Portuguese and Spanish explorers decided to take them back to Europe in hopes to trade them as an exotic commodity. As trade routes opened connecting the Americas to Asia, achiote travelled initially to the Philippines via the Manilla Galleon Trade route that began in 1565. This significant trade route which lasted for around 250 years, connected Acapulco in Mexico to Manilla in the Philippines and was one of the largest world exchanges of spices, people, porcelain and precious metals in history.

Once achiote arrived in the Philippines it was adapted into their cooking, which inspired interest from Indonesia and other neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia. Through sea trade routes, it spread to Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

As colonisation in the Caribbean took place from the 15th Century onwards, the Caribbeans started incorporating achiote as a colouring and as a paste for marinating meats. The Transatlantic Slave trade also impelled Africans to work in the Caribbean and Americas as plantation workers and servants, enabling the exchange of commodities, including achiote.

Credit: sweetlifebake.com

What does achiote taste like and how to use it?

Achiote has a subtle floral and peppery taste, providing warmth to dishes like nutmeg. Despite its mild taste, adding achiote to a dish can transform it tremendously. It is used as a popular food dye to colour cheeses, candy, ice cream, and various meat products.

It can be used as a marinade for cochinita pibil, a Yucatecan speciality in Mexico, added to Brasilian fish moqueca, infused in Puerto Rican arroz con pollo or added to a Filipino Kare Kare.

The seeds of the achiote fruit can be used as is or are treated in several ways to extract optimal colour and flavour before it is used as a culinary ingredient.

Popular preparations of achiote seeds before incorporating them into a dish are:

Achiote Oil or Water

The seeds are submerged in oil or water and heated to impart colour and a touch of flavour.

Achiote paste

Vinegar is used with ground seeds and additional herbs or spices to form a paste.

Achiotina

Is the result of a flavour and colour extraction through heated animal lard.

Non-Culinary Uses

The achiote fruit and leaves are used in a variety of cultures around the world as a diuretic, wound dressing, anti-venom, and even a cure for muscle aches and pains. In a more altered form, it is used widely to colour creams and lipsticks in the cosmetic industry and as an additive to a variety of medicines.

This wondrous little plant has managed to place itself subtly into all the corners of the world, through a history of colonisation, trade routes, and cultural exchanges over many years. Achiote is another beautiful example of how food history and culture are so interconnected and can tell exciting tales that evolve over time.